Minneapolis-St. Paul Int’l Leverages Technology & Advisory Panel to Expand Universal Access Far Beyond Legal Requirements

Video-relay sign language interpreting for travelers who are deaf or hard-of-hearing. Camera-equipped glasses that facilitate real-time navigational cues for visually impaired passengers. Flow-through elevators and restrooms specifically designed for wheelchairs. Improved pictogram signage to communicate crucial wayfinding directions without written language.

If this sounds like a futuristic, pie-in-the-sky vision of airport accessibility, it’s not. All of these measures and more already are in place at Minneapolis-St. Paul International (MSP), one of a growing number of airports that are going well above minimum standards required by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

“Our goal is to be the world’s most accessible airport,” says MSP Operations Director Phil Burke. “We want to create that brand, as well as get the message out that any airport can do this. It just takes commitment.”

|

facts&figures Project: Equitable Accessibility Location: Minneapolis-St. Paul Int’l Airport Program Elements: Video sign-language interpreting; tech-assisted navigation for sight-impaired visitors; flow-through elevators; wheelchair-accessible dining tables; all restroom sinks & stalls at accessible heights/dimensions; airport tours/prep sessions for passengers with special needs Funding: General airport revenue Facilities Design: Alliiance Key Stakeholders: Travelers with Disabilities Advisory Committee; Open Doors Organization Video Sign-Language Interpreting: Voiance Language Services Cost to Airport: $2.49 per minute for service; iPads to provide connection Navigation System for Sight-Impaired Visitors: Aira Tech Corp. Key Benefits: Improving access; treating all passengers equitably; exceeding Americans with Disabilities Act mandates |

Burke elaborates that MSP’s goal is equitable access rather than equal access. Equitable facilities provide everyone with the same experience while equal facilities often mean separate, stand-alone accommodations and features just for travelers with impairments, he explains.

Wider restroom stalls are a classic example of MSP’s approach. Instead of adding one or two wider stalls per restroom, the airport made all of its stalls wider. Similarly, it didn’t install one shorter sink among a bank of standard-height fixtures; all sinks stand at a wheelchair-accessible height. “There’s a difference between equal and equitable,” Burke emphasizes.

Alliiance, the Minneapolis firm that designed the project, embraced and implemented that important nuance. One wider restroom stall or appropriate-height sink isn’t sufficient if it’s already in use when someone else needs it, explains Eric Peterson, an Alliiance principal and terminal planner/designer. “Providing equitable access everywhere eliminates that differential,” he notes. “It’s much better than making someone wait or making them travel farther into the terminal to find an available stall.”

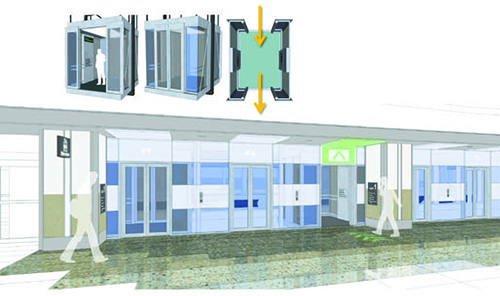

Another good example is pass-through elevators, which allow users to enter on one side and exit through the opposite side. The two-door design eliminates the need to turn around to exit—a difficult maneuver to make from a wheelchair, especially when the elevator is packed with other travelers. “No one has to change their direction; everyone has the same experience,” explains Peterson.

Valuable Advice

Airport officials and architects don’t intentionally ignore the needs of travelers with impairments, emphasizes Peterson. Fully accommodating everyone, however, isn’t always top-of-mind.

“Most architects try to serve the public well; it’s part of our professional obligation,” he says. “However, too many projects just focus on meeting minimum ADA standards. MSP has made a concerted effort to go above and beyond—to be organized about this and maximize equitable accessibility. That’s a much more deliberate approach than just relying on the experience and good intentions of planners and designers.”

The key to MSP’s ongoing efforts is a structured approach, says Peterson. In 2014, the airport added a Travelers Advisory Committee to its existing Customer Service Action Council. The committee includes 26 airport staffers and frequent flyers who collaborate quarterly to improve the overall travel experience at MSP. For accessibility issues, the rubber meets the road via an adjunct Travelers with Disabilities Advisory Committee. Also created in 2014, it includes 28 members, primarily local residents with a variety of different disabilities who represent the needs of their wider communities.

The two advisory groups provide meaningful input regarding facility improvements, notes Burke. “The organizational structure is not that complicated,” he adds. “Any airport can do it—and should be doing it.”

Real-life perspectives from people with disabilities are invaluable to MSP’s quest for equitable access. Burke points to new holdroom seating as a prime example. Chairs marked with the familiar wheelchair symbol used to be blue, while all other nearby chairs were black. Committee members asked airport officials to make the designated chairs black, too (but retain the wheelchair symbol), so users wouldn’t feel different from everyone else.

“The takeaway from this is that we used to make assumptions based on good faith,” Burke explains. “We thought it was a great idea to set those chairs apart; but input from the committee made us realize that there’s no need to call special attention to them with color. It all goes back to providing the same experience for all our travelers.”

Change Isn’t Easy

Going above and beyond ADA compliance wasn’t always smooth sailing, Burke acknowledges. “I understand that most people think it will cost more money, or that it could divert revenues to design facilities to a higher level than code requires,” he comments. “But that’s not the case at all. In fact, you can flip that around: If you design facilities to a more universal code, more people can use those facilities, and you can make more money.”

He says that it’s difficult to pinpoint the exact cost of MSP’s above-and-beyond accessibility efforts, but the lion’s share of expenditures for improvements have been minimal. Some—such as reprogramming electronic signage—cost nothing at all. For example, variable-message signs on the departures level used to flash two different messages: first a wheelchair symbol, then the words “Doors 2 and 4.” When members of the advisory committee indicated it was unclear exactly what services were available at the doors, the airport added a third message: “Assistance available.”

“We literally made the change on the fly during a TDAC (Travelers with Disabilities Advisory Committee) meeting,” Burke says. “It was a great example of the airport listening to the disabled community.”

As another example, Peterson cites the airport’s decision to install new tables in dining areas. Although two-person tables supported by a central pedestal are standard in most airports, the pedestals prevent wheelchairs from rolling far enough under the table for comfortable use. The solution at MSP? Install two-and four-person tables supported by corner legs instead of central pedestals.

“Now, someone in a wheelchair can sit in every part of our food court facilities,” Burke points out. “That’s essentially a no-cost difference— just an awareness on the front end of designing that creates a more uniform experience for everybody.”

Another subtle change involved shifting from escalators to elevators as the dominant means of vertical transportation. Elevators (especially pass-throughs) are more convenient and safer for mobility-challenged people than escalators. As such, Peterson says it simply make sense to design more elevators into facility plans.

“Typically, escalators are located in central areas, and elevators are way over in some corner,” he explains. “If you have more elevators, centrally located and clearly marked, it’s easier and more accessible for everybody.”

In October, MSP opened a station that repairs and services mobility equipment such as wheelchairs and scooters. After testing the new concept, the concession was ready for customers during the busy Thanksgiving and winter holiday travel seasons. The station is run by Scootaround, which also provides replacement equipment and offers short-term rentals.

New Technology

While many accessibility programs center on mobility challenges, MSP broadened its efforts to address the needs posed by other disabilities, such as sight and hearing impairments. A good example is video-relay interpreting for visitors who use American Sign Language.

The ADA code requires TTY (TeleTYpewriter) devices at a limited number of pay phones for people who are deaf or hard-of-hearing, but the airport chose a more modern approach. Input from its advisory committee led MSP to deploy a video-based option from Voiance Language Services.

Here’s how it works: Travelers can pick up an iPad at any information booth, and an assistant helps them connect on screen with an interpreter who is fluent in American Sign Language. “It turns into a three-way form of communication between the interpreter, the customer and the assistant who helped the customer log in. It’s working out beautifully,” reports Burke.

The airport pays $2.49 per minute for the service, with monthly bills amounting to a few hundred dollars. Multiple iPads are available at each of its 10 information booths, with coverage in both terminals.

In a similar vein, MSP is testing a tech-based solution to help vision-impaired customers navigate the airport. The system, developed by Aira Tech Corp., includes eyeglasses with cameras mounted on the frames. When a user dons the glasses, the camera transmits whatever the wearer is “seeing” to a remote assistant, who verbally narrates whatever route the airport visitor takes.

“The glasses and the camera literally become the eyes of the person who’s blind,” Burke explains. “They tell them that there’s a bathroom on the right, for instance, or what airline gate they’re passing by. It’s like a virtual escort.”

MSP also works to address the special needs of many other visitors, including those with cognitive and psychological challenges and height and size extremities. For many years, personnel have offered monthly tours and programs designed to familiarize travelers with autism (especially children) with the airport’s layout and process. (For more details on the program, consult our Sept. 2014 issue.) In 2015, MSP expanded the program to include any traveler who wants to feel more comfortable with the airport experience. The goal is to reduce stress for customers by providing practice with typical procedures such as entering the terminal, checking in for a flight, going through a security checkpoint, boarding an aircraft and finding the right seat.

Gender-neutral restrooms are a welcome addition for transgender customers and families or caretakers assisting opposite-gender travelers. The airport also offers special facilities for pregnant and nursing mothers, the advanced elderly and guests with service animals. Moreover, plans are in place to add adult changing stations in 2018 or 2019.

Growing Enlightenment

As more airports raise their standards for accessibility, architecture and planning firms will need to follow suit. Peterson predicts that they’ll find the process gratifying.

“At Alliiance, we enjoy creating places where people can live their lives to the fullest,” he relates. “Airport and travel are exciting things…and to be able to make a difference in travelers’ lives is a strong motivator for us. Through working with MSP, our awareness has grown considerably; they have opened our eyes to the importance and power of equitable design.

“But the bigger message is what it takes in terms of commitment and internal structure for airports to make this happen,” he adds. “It has to become a cultural thing for airports like MSP, as well as the planners and designers working with them.”

Burke, who recently teamed with Peterson to present a seminar on equitable accessibility at a SMART Airports and Regions conference, emphasizes that there are compelling business reasons for airports to make it a priority when planning new facilities or redesigning old ones. But he also recognizes that improving access is about more than costs and revenue. As he says, “At the end of the day, it’s just the right thing to do.”

|

Work in Progress

“I had to fly to Montgomery, Alabama, and it was a nightmare,” recalls Lipp, who now uses a leg brace and cane, and occasionally rides an electric scooter for longer distances. “So I started Open Doors [in 2000] for a pretty self-serving reason…there was no advocacy group pushing for accessibility in the travel and tourism industries. Disabled people didn’t have access to the keystones of travel—places like airports, hotels, cruise ships and restaurants, not to mention theaters, museums and so forth.” Airports that don’t make facilities as accessible as possible do so at their own risk, he notes. Each year, approximately 6 million air travelers self-identify as having a disability, and they spend an average of $20 per person at airports. Conservatively, that amounts to $120 million a year. Lipp suspects the spending total may be even higher, because many people won’t admit they have a disability when asked. “I know of one big airline that’s pushing 1,500 wheelchairs a day,” he notes. On an overall basis, Lipp describes the current state of airport accessibility as a work in progress. “That says it all: good, bad and indifferent,” he explains. “We’re not there yet, but people aren’t saying ‘no,’ either.” Lipp refers to the biggest obstacles as the two M’s: mindset and money. It’s not that airport executives fail to care about accessibility; most simply lack a deep awareness of the issue, he explains. “My job is to touch someone at that executive level…so that it (accessibility) becomes a bigger initiative.” When awareness isn’t an issue, funding often still is an impediment. But improvements don’t have to be expensive, Lipp emphasizes. “Think about it: You substitute door levers for door knobs. How hard is that? Or make bathroom stalls longer and add some handrails, so they’re all ambulatory-accessible. That doesn’t cost all that much, and it’s good for everybody.” Lipp highlights Minneapolis-St. Paul International (MSP) as a national leader in airport accessibility. He commends its attention to detail, right down to the mechanics of restroom doors. Instead of closing completely, they stop about a quarter-inch from the doorframe, so blind people can use their canes to discern if a stall is occupied. “That’s just good design,” he comments. Between new construction and renovation efforts, opportunities to improve accessibility abound on many fronts. “Airports always seem to be planning new projects,” he explains. “And when they do, they need to make sure there’s a seat at the table for architects who understand good design.” Lipp also encourages airport executives to do some role-playing to better understand the need for improvements. Put on a blindfold when clearing the security checkpoint; or navigate the concourse in a wheelchair, for instance. “It’s like secret-shopping your own airport,” he explains. Moreover, he advises airports to form accessibility advisory committees, like the one created at MSP. (See Page 9 for more details.) Looking ahead, Lipp says that growing consciousness bodes well for the future of improved accessibility at airports. “I see it spreading across the globe, not just in the United States; and that’s very cool,” he muses. “We’re making this a reality.” |

2022 Charlotte Douglas International Airport Report of Achievement

Giving back to the community is central to what Charlotte Douglas International Airport and its operator, the City of Charlotte Aviation Department, is about, and last year was no different.

Giving back to the community is central to what Charlotte Douglas International Airport and its operator, the City of Charlotte Aviation Department, is about, and last year was no different.

Throughout 2022, while recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, we continued our efforts to have a positive impact on the Charlotte community. Of particular note, we spent the year sharing stories of how Connections Don't Just Happen at the Terminal - from creating homeownership and employment opportunities to supporting economic growth through small-business development and offering outreach programs to help residents understand the Airport better.

This whitepaper highlights the construction projects, initiatives, programs and events that validate Charlotte Douglas as a premier airport.

Download the whitepaper: 2022 Charlotte Douglas International Airport Report of Achievement.

When spinal surgery forced Eric Lipp to use a wheelchair for two years, the experience provided an epiphany that prompted him to establish the Open Doors Organization, a nonprofit group dedicated to improving accessibility in travel and tourism for people with disabilities.

When spinal surgery forced Eric Lipp to use a wheelchair for two years, the experience provided an epiphany that prompted him to establish the Open Doors Organization, a nonprofit group dedicated to improving accessibility in travel and tourism for people with disabilities.