Peoria Int'l Decreases Bird Strikes With Rodent Control Campaign

Gene Olson enjoys gazing from the sweeping windows in his office at General Wayne A. Downing Peoria International Airport (PIA). Too often, however, the picturesque view is spoiled by birds-more specifically by thoughts of the damage they could cause to aircraft operating at the central Illinois airfield.

In fact, a bird caught Olson's eye during the telephone interview for this article. "As we speak, I'm looking out over the airfield, and there goes a flipping hawk, flying right across the midfield area," comments the director of airports for Peoria's Metropolitan Airport Authority. "It's flying real low and just landed on a windsock."

Birds are a common sight for Olson, but not nearly as common as they were before PIA launched an initiative to manage the growing population of predator species in the area. Red-tailed hawks, American kestrels and other birds of prey were feasting on voles thriving in fields around PIA, and the airport was consequently experiencing increased bird strikes.

facts&figures facts&figuresProject: Wildlife Management Location: General Wayne A. Downing Peoria (IL) Int'l Airport Airport Operator: Metropolitan Airport Authority of Peoria Strategy: Eliminating food source of predator birds (voles) with pesticides Results: Reduced bird population by 60+%; decreased bird strikes 20+% Approx. Cost: $10,000 Funding: Illinois Air National Guard; Metropolitan Airport Authority of Peoria Timeline: Pesticide treatment July-Aug. 2015 Project Manager: Airport Wildlife Hazards Program, a division of U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Wildlife Services For Airport-Specific Incident Information: Consult the Federal Wildlife Strike Database at wildlife.faa.gov/database.aspx |

In summer 2015, however, PIA partnered with the USDA Wildlife Services' Airport Wildlife Hazards Program (AWHP) to eliminate the voles. Since then, the airport has reduced its population of problematic birds by more than 60%, and bird strikes have decreased by more than 20%.

According to the FAA Wildlife Strike Database maintained by AWHP, PIA has experienced 150 wildlife strikes in the last five years. However, only six have occurred since November 2015 (after the vole control program was in full swing). The most common bird strikes at the airport since 2011 involved American kestrels, the smallest falcon in North America. Others involved red-tail hawks and non-predators such as killdeer and barn swallows. FAA records also note strikes at PIA involving a bat and a great horned owl.

Although the airport has had wildlife strikes that resulted in aircraft damage, Olson doesn't categorize any of the incidents as scary. "I don't recall anyone on the civilian side needing to make an emergency landing due to an air strike,"

he notes.

The airport serves four scheduled airlines as well as a steady flow of cargo planes that land and take off at all hours. It's also home to the 182nd Airlift Wing of the Illinois Air National Guard, which flies C-130s. In 2015, PIA serviced a record-high 642,000 passengers (321,000 enplanements).

Growing Problem

Olson says it became clear in recent years that PIA needed to address its predator bird population. "We would see raptors perched on anything that had a horizontal surface," he laments.

AWHP specialists note that because of their size, hawks and other raptors often cause damage if they strike an aircraft. Their behavior also makes them dangerous, adds Olson. "Hawks are the fighter pilots of the sky," he says. "They think they can outfly you, so they wait too long to get out of the way and then you smack [into] them. Seagulls are dangerous because they tend to flock, but they're stupid."

Per FAA regulations, PIA conducts wildlife hazard assessments after bird strikes and prepares a management plan to identify specific actions it will take to mitigate the risk of wildlife strikes on or near the airport. Like other airports, it goes to great lengths to minimize the attractiveness of open areas that provide food, water and cover to a wide range of animals. Preventive wildlife management measures at PIA include 10-foot fencing and endophytic grass, which tastes bad to geese.

"You'll hear the term 'integrated pest management' thrown about," Olson remarks. "There are a lot of contractors out there who throw the term around, but they don't know how to practice it."

Eliminating Sustenance

Hunter Ray, a Wildlife Services AWHP-qualified airport wildlife biologist stationed at PIA measured the bird population on and around the airfield and enacted a commonly used technique: encouraging predator birds to relocate by eliminating their food source. At PIA the targeted food source was voles, small rodents often mistaken for mice.

"There are a lot of things you can do with wildlife at airports," explains Michael J. Begier, national coordinator of AWHP. "The best and most efficient in terms of money and time is to change the habitat. If you can figure out why they're there and you can change the habitat to make it not attractive, that's the goal."

Other strategies employed by AWHP include eliminating or reducing trees, shrubs and other plants that provide food, shelter and roosting sites; scaring birds away with distress signals, pyrotechnics or other methods; and draining streams or wet grassland areas of standing water.

At PIA, the Air National Guard and the Metropolitan Airport Authority of Peoria shared the cost of the $10,000 bird management project. The airport authority purchased pesticide to exterminate the voles, and the Guard paid for the labor to apply it.

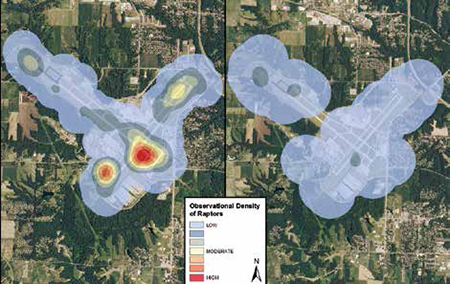

According to Ray's measurements 12 months before and after the pesticide treatment, the airport experienced a 64% reduction in raptors compared to the same time period the prior year. Wildlife strikes with raptors also dropped 21%. Before-and-after aerial mapping of the predator population was illuminating (see 64).

"A picture is worth a thousand words, but maps are worth a little bit more," says Jason Kougher, an AWHP staff biologist. Kougher oversees day-to-day geospatial data collection at airfields and provides wildlife mapping to identify "hot spots." At PIA, the hot spots pinpointed areas where raptors were observed.

"When you depict these surveys, you end up with large circles identifying where the raptors prefer to look for food," explains Kougher. "If we can show a map of the wildlife hazards story, whether they are habitat hazards or wildlife species hazards, then we can convey that story a lot better; and airport management can allocate those resources to fix the problem a lot more efficiently."

"When you depict these surveys, you end up with large circles identifying where the raptors prefer to look for food," explains Kougher. "If we can show a map of the wildlife hazards story, whether they are habitat hazards or wildlife species hazards, then we can convey that story a lot better; and airport management can allocate those resources to fix the problem a lot more efficiently."

What Are the Odds?

According to SKYbrary, a British-based electronic repository of aviation safety information, aircraft damage from bird strikes differs according to the size of aircraft involved. Small, propeller-driven planes are more likely to experience structural damage, while larger jets are more susceptible to engine ingestion. Partial or complete loss of control may be the secondary result in either scenario. Bird strikes can also cause flight instruments to malfunction.

Interestingly, SKYbrary reports that military aircraft, like those flown out of PIA by the Air National Guard, experience more problems with damaging bird strikes than civilian aircraft, because military flights are more often conducted at low levels. It is not uncommon for large birds to shatter the windows of low-flying military aircraft, which is one of the reasons jet pilots' helmets have visors.

With military traffic and business jets carrying passengers to and from Caterpillar's corporate headquarters in Peoria, PIA incurs both types of risk.

AWHP reports that about three dozen bird strikes occur every day at U.S. airports, but only 6% to 7% result in aircraft damage.

Of course, the most famous incident forced Capt. "Sully" Sullenberger to perform a spectacular emergency landing in the Hudson River after multiple bird strikes caused both engines of a US Airways jetliner to fail. All 155 passengers and crew aboard the Airbus A320 survived the January 2009 incident, inspiring the nickname "Miracle on the Hudson" and a feature film.

PIA hasn't experienced any movie-worthy incidents, and Olson is intent on keeping it that way. He still vividly recalls a bird strike he experienced when flying as a commercial pilot in Indiana nearly 20 years ago. "I was flying at 10:30 at night about 5,500 feet up and hit a bird. My first thought was, 'What the heck is a bird doing a mile up at 10:30 at night?' Talking to a biologist later, I learned that is absolutely the worst altitude to pick during migratory seasons."

Frequently Asked Wildlife Management QuestionsQ: When do most bird strikes occur? Source: faa.gov |

2022 Charlotte Douglas International Airport Report of Achievement

Giving back to the community is central to what Charlotte Douglas International Airport and its operator, the City of Charlotte Aviation Department, is about, and last year was no different.

Giving back to the community is central to what Charlotte Douglas International Airport and its operator, the City of Charlotte Aviation Department, is about, and last year was no different.

Throughout 2022, while recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, we continued our efforts to have a positive impact on the Charlotte community. Of particular note, we spent the year sharing stories of how Connections Don't Just Happen at the Terminal - from creating homeownership and employment opportunities to supporting economic growth through small-business development and offering outreach programs to help residents understand the Airport better.

This whitepaper highlights the construction projects, initiatives, programs and events that validate Charlotte Douglas as a premier airport.

Download the whitepaper: 2022 Charlotte Douglas International Airport Report of Achievement.