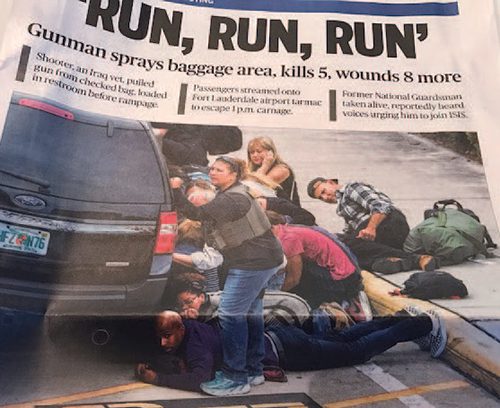

Early last year, Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport (FLL) in Broward County, FL, experienced the deadliest airport shooting in U.S. history when a passenger killed five people and sent six others to the hospital with injuries. More than 50 others were hospitalized for chest pains, low blood sugar, broken bones, etc. incurred while fleeing the scene and during a subsequent stampede triggered by false reports of another shooting.

Airport Director Mark Gale and other FLL executives have been notably candid sharing their reflections about the horrific tragedy for the good of the overall industry. “When you think of the tens of millions of people who traverse through airports every day, there is no foolproof way to prevent the actions of a single individual,” Gale says solemnly. “However, there are lessons in this incident that can help every airport—from a small general aviation facility to a large mega-hub—be better prepared.”

Mike Nonnemacher, chief operating officer at FLL, summarizes one overarching theme of airport’s message this way: “You can mitigate a lot of things by having a good, solid plan, practicing that plan and being ready. You can mitigate the time it takes to respond, the impact of the response and the confusion that follows.”

|

Project: Refining Emergency Response Location: Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood (FL) Int’l Airport Catalyst: Mass shooting in Terminal 2 baggage claim area on Jan. 6, 2017 Shooting Casualties: 5 people killed, 6 hospitalized with injuries Total Injuries: 50+ people hospitalized with chest pains, broken bones, etc. incurred while fleeing the scene & during subsequent stampede triggered by false reports of another shooting 90 minutes later Post-Incident Review: Ross & Baruzzini Key Changes: Relocating emergency operations center & streamlining identification procedures for personnel access; improving communications systems to address passengers & airport personnel; enhancing active shooter training for airport employees & holding practice drills New Communication System: Integrated Public Alert & Warning System Public Address System for Ramp: XYZ Personal Effects Management: BMS CAT |

In the aftermath of the mass shooting, FLL hired aviation consultant Ross & Baruzzini to help evaluate the incident and the airport’s associated response. FLL executives have since addressed, or are in the process of addressing, all topics identified in Ross & Baruzzini’s assessment. Specific projects include relocating the emergency operations center and revising response procedures for key personnel; improving communications systems; and enhancing existing active shooter training for airport employees.

Lessons Learned

To understand the extent of what has occurred at FLL in the last year or so, Gale encourages peers at other airports to take a closer look at what ensued on Jan. 6, 2017.

The shooter waited at a baggage carousel in Terminal 2 for several minutes before being paged to pick up his bag at a baggage service office. He took the bag, which contained a 9 mm semi-automatic pistol, into a nearby bathroom, where he loaded the weapon and then stuck it in the waistband of his pants. Minutes later, he pulled out his gun and began shooting.

It is at this point that Gale begins most of his conversations about planning for an active shooter incident. He notes that he has reviewed the short video clip of the event hundreds of times, and always comes to the same conclusion: “You cannot tell the individual has a gun in his waistband. You can’t tell what he is about to do. There is no behavior that would have caused people to become concerned, panicked or alarmed, until he pulls out his weapon and starts to fire.”

Deputies stationed at the airport raced toward the shooter as he fired 14 rounds. Within 85 seconds, law enforcement had him in custody. But he had already done his damage, and people lay dead and wounded.

As soon as police officials arrived on the scene, they began trying to determine the identity of the shooter, where he came from and whether he was caught on camera with anyone else who could be a companion or an accomplice. “This is all taking place as [emergency response] officials are tending to fatalities and injuries,” Gale advises. “As you can imagine, it was a chaotic and crazy scene. But I think the airport staff, law enforcers, fire/rescue personnel—everyone—did a good job on that particular piece.”

It wasn’t until 90 minutes later when things began to unravel a bit, he adds. That’s when false reports of additional gunshots caused widespread panic among travelers, airline personnel and airport employees in all four terminals. Many took cover inside, but thousands rushed out emergency exits onto the tarmac. News reports used words such as chaos, turmoil and pandemonium to describe the scene.

The crowd’s reaction was not entirely predictable, notes Gale. “I know there are some who would argue that the incidents at LAX or JFK should have been a wakeup call, but I don’t think that we could have envisioned a secondary incident with the magnitude of what we experienced. Nor could we have anticipated that it would cause such a panic and spontaneous evacuation from our building,” he remarks.

“You’ve heard the saying, ‘Hindsight is 20/20’? If we had to do it again, there are a number of things we would do differently.”

Here are nine of his top recommendations for other airport operators:

Recommendation #1: Ensure Access for Critical Airport Personnel

The day of the shooting, Nonnemacher served as incident commander at the airport’s emergency operations center (EOC). The industry veteran, with more than three decades of aviation experience, oversaw recovery efforts, including logistic coordination with law enforcement.

Nonnemacher was notified within 1½ minutes of the shooting and was able to reach the EOC to begin operations within 11 minutes. But other key staff members were delayed reaching the EOC because police had erected barricades while they investigated reports of a second shooter.

Nonnemacher was notified within 1½ minutes of the shooting and was able to reach the EOC to begin operations within 11 minutes. But other key staff members were delayed reaching the EOC because police had erected barricades while they investigated reports of a second shooter.

“If you were on airport property but away from the terminal, you didn’t get in—even if you had an airport ID,” explains Gregory Meyer, public information officer for Broward County Aviation Department, FLL and North Perry Airport. “Law enforcement was doing its job; but this meant critical airport personnel couldn’t get in until they figured out how to get in. It took me 10 minutes to talk my way in, and I’m the airport PIO.”

When FLL transitioned to addressing corrective measures, this is the first problem it tackled and solved.

“Airports absolutely must have a robust methodology of identifying critical responders,” advises Nonnemacher. “Even our own airport CEO was denied access to certain areas of the airport during a drill; and that was just a drill. We had to solve that problem.”

These days, the airport requires a small group of key employees to carry special identification badges that indicate their status regarding emergency response. FLL also trained local law enforcement how to recognize and respond to the new badges. Now during an emergency, select airport employees will be able to flash their badges at assigned checkpoints for quicker access to the airport EOC.

Access has also been tiered. For every EOC position, the airport now designates and trains primary, secondary and tertiary responders. Primary responders are granted access first; secondary and tertiary responders gain entry when they are summoned. The new structure reduces the number of people attempting to enter the EOC at one time and ensures coverage if an event spans multiple days.

Access has also been tiered. For every EOC position, the airport now designates and trains primary, secondary and tertiary responders. Primary responders are granted access first; secondary and tertiary responders gain entry when they are summoned. The new structure reduces the number of people attempting to enter the EOC at one time and ensures coverage if an event spans multiple days.

“During the 2017 incident, we had a significant amount of burnout among the personnel who responded, because the response lasted several days,” notes Nonnemacher.

Recommendation #2: Analyze Location of Emergency Center

Like many airports, FLL used to house its EOC inside the terminal proper. It was located in Terminal 3 to facilitate quick response to situations within all four terminals. However, during the active shooter incident, police put that area in lockdown when reports of shots elsewhere rolled in. As a result, no one could enter or leave the crucial response center.

FLL has since moved its EOC to another building away from the terminals.

“It’s now much easier to get to,” says Nonnemacher. “If we seal off the terminal building with a police barricade, we can still access the EOC because it is in a separate building.”

“It’s now much easier to get to,” says Nonnemacher. “If we seal off the terminal building with a police barricade, we can still access the EOC because it is in a separate building.”

Locating the facility elsewhere also ensures that EOC personnel can maintain access to communications systems; electrical power; and heating, ventilation and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems—essential elements when responding to an incident. During the 2017 incident, the EOC had enough power to run its operations equipment but lacked sufficient power to operate the HVAC system.

“The new EOC, which we christened during Hurricane Irma, performed beautifully because the HVAC system and all critical components worked under a generator. The generator powered everything that we needed, and we housed people for four days during that event,” Nonnemacher reports.

Recommendation #3: Provide a Staging Area for Outside Responders

While extra assistance is needed and appreciated during an emergency, processes must be in place to handle the influx of responders, Gale advises. When an estimated 2,600 police officers descended on FLL after the shooting, a lack of familiarity with the airport’s layout and operational policies hampered their response efforts.

“When the call went out about there being a shooter at the airport, law enforcement had a self-deployment issue,” Nonnemacher explains. “They came in droves and set up checkpoints and blocked entrances to the airport. This included officers who were not in our district.”

“When the call went out about there being a shooter at the airport, law enforcement had a self-deployment issue,” Nonnemacher explains. “They came in droves and set up checkpoints and blocked entrances to the airport. This included officers who were not in our district.”

In retrospect, FLL recommends following the National Incident Management System (NIMS), a program from the Federal Emergency Management Agency that provides procedures and protocols for all responders—federal, state, tribal and local. NIMS guidelines are designed to help organizations manage the complicated logistics of emergency response.

Per FLL’s new system, law enforcement responding to emergencies at the airport now report to a pre-set staging area. From there, officers are deployed to specific locations where they are most needed—to search buildings, secure perimeters, help the injured, etc.

The airport has also conducted outreach programs to help educate local police and other first responders about its facilities. Maps and blueprints of the terminals and associated infrastructure were distributed on thumb drives and will soon be distributed on heavy-duty tablets.

Recommendation #4: Develop Backup Communication Systems

As police and fire officers answered calls for backup and converged on FLL, they encountered radio problems. “The crush of users sent the system into a ‘fail-soft’ mode, and all connections between responding agencies were lost,” said the Sheriff’s post-incident report. “Dispatchers were not able to quickly reconnect groups and told all units to stop transmitting until the radio bridges could be restored.”

This took about four minutes, but then the system began to “throttle,” which resulted in garbled transmissions.

Unfortunately, that was only part of the communication challenges. Another issue involved the passengers and employees who ran outside to the ramp area instead of sheltering in place inside the terminal. The airport was making announcements on its public address system and social media, but many passengers left their cellphones and some employees left their work radios in the terminal when they fled, and the public address system was only broadcasting messages inside the terminal. “You need to be cognizant of the fact that people will abandon their communication devices when they are running for their lives; so you need multiple modes of communication,” Nonnemacher counsels.

FLL now has more robust communication plans and systems in place, and is designing a new public address system for use on the ramp. It will also be using the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS), which is designed to provide public safety officials with an effective way to alert and warn the public about serious emergencies via a single interface. This modernized version of the nationwide alert and warning infrastructure can be integrated into local systems that use Common Alerting Protocol (CAP) with IPAWS infrastructure.

FLL now has more robust communication plans and systems in place, and is designing a new public address system for use on the ramp. It will also be using the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS), which is designed to provide public safety officials with an effective way to alert and warn the public about serious emergencies via a single interface. This modernized version of the nationwide alert and warning infrastructure can be integrated into local systems that use Common Alerting Protocol (CAP) with IPAWS infrastructure.

“In Florida, this system is maintained through the Florida Division of Emergency Management,” says Nonnemacher. “We simply call them up and ask that they broadcast a specific message on IPAWS, and it goes out to cellphones in a geofenced area, much like an Amber Alert.”

For instance, if 100 people gathered on the southside of the airfield by the fence line, they could receive an alert with information about what’s transpiring and what to do if just one person had a cellphone.

Understanding that people may not always have their cellphones, FLL purchased 50 bullhorns with a 1,200-foot radius capability. The new low-tech equipment will allow airport officials to make announcements in parking facilities, on the terminal roadway, in the terminal and on the airfield. FLL also maintains public address systems in its operations and security vehicles.

Recommendation #5: Train Employees in Specific Response Techniques

Before the Jan. 6, 2017, incident, FLL had trained its employees according to the Run, Hide, Fight active shooter protocol from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). The program instructs people under siege to run toward a pre-determined escape route while leaving behind belongings such as cellphones, purses, etc. Once there, they should hide outside the view of the shooter(s), block the entry and/or lock the doors. Using physical aggression to incapacitate a shooter—“fight” in the program title—is recommended as a last resort and only in imminent danger.

Although the Run, Hide, Fight training FLL employees received is specifically designed to save lives, some say they didn’t know what to do or how to help. “Many employees have gone through our security training, but valid points were raised in discussions afterward that led us to believe more training is needed,” Gale reflects.

As a result, FLL plans to build on the DHS curriculum by providing practical instructions for employees who may be hiding or in lockdown while law enforcement does its job. “One of our biggest takeaways was that while law enforcement is in charge, there needs to be recognition that thousands of people are in a variety of different locations and need support. They are going to need a bathroom, water and food, and more than anything else, they are going to need information about what’s going on,” Gale says.

As a result, FLL plans to build on the DHS curriculum by providing practical instructions for employees who may be hiding or in lockdown while law enforcement does its job. “One of our biggest takeaways was that while law enforcement is in charge, there needs to be recognition that thousands of people are in a variety of different locations and need support. They are going to need a bathroom, water and food, and more than anything else, they are going to need information about what’s going on,” Gale says.

The main goal of FLL’s additional training is to teach employees how to deal in an emergency. “It could be a shooter, an airplane crash, a fire or tornado,” he relates. “This will just give them the tools they need to deal with the situation at hand. And, we will have 15,000 people all receiving the same training, versus 15,000 people who have received 150 different versions of the same training.”

The supplemental material will cover important specifics, adds Nonnemacher. “This training will educate employees on how to communicate, how to report where they are, what their condition is, and what to say to people who are injured.

“It will also educate them on what to expect from first responders,” he continues. “During an active shooter situation, law enforcement is going to run into gunfire; they are not going to stop to help others.”

In February, a syllabus for additional training was approved by the Broward County Board of Commissioners, and the airport was developing a new training program with assistance from Safety and Security Instruction of Phoenix. Training is expected to begin in August; Nonnemacher estimates that it will take about six months to cycle all 15,000 FLL employees through the new program.

To help achieve its 100% training goal, FLL plans to offer materials in a cloud-based format, so employees can complete the curriculum in a variety of locations, even from home. Topics covered during the paid, mandatory training will include airport familiarization, what to expect during initial response efforts, how to interact with law enforcement and basic first aid.

A locally created active shooter video will replace the DHS video that is currently used, and a section on everyday customer service will also be added. Gale notes that the heart of the training will still be emergency response, but officials do not want to miss an opportunity to remind employees that everyone is an ambassador for the airport and their interaction with the traveling public is incredibly important.

A locally created active shooter video will replace the DHS video that is currently used, and a section on everyday customer service will also be added. Gale notes that the heart of the training will still be emergency response, but officials do not want to miss an opportunity to remind employees that everyone is an ambassador for the airport and their interaction with the traveling public is incredibly important.

Recommendation #6: Provide Basic Necessities

After the shooting, travelers were stranded at FLL for up to 10 hours.

“Getting supplies to people was very difficult to do,” recalls Nonnemacher. “We did make arrangements, but law enforcement did not want any extra movement.” Eventually, airport personnel received permission to escort people to/from nearby restrooms and bring portable restrooms from construction sites to the ramp.

“Once we were off lockdown, we grabbed all the snacks and water we could from vendors to give to passengers,” says Nonnemacher.

Now, FLL keeps approximately 10,000 snacks and bottles of water on hand in a warehouse. Gale notes that it is important to get “simple necessities” such as food, water, blankets, pillows, diapers, baby formula, etc. to people as soon as possible. FLL rotates its stock to prevent spoilage and waste.

The airport also stockpiles basic medical supplies and bleeding kits. “This way, when we have an incident, we don’t have to wait for first responders; we have enough to get us started,” he explains. “We are trying to be as proactive as we can for what we hope never happens again.”

Recommendation #7: Create a Plan to Return Personal Property

When people are forced to flee for lives, the belongings they leave behind create an eerie tableau. After the shooting at FLL, about 23,000 items were strewn haphazardly throughout the airport—everything from suitcases and cellphones to baby strollers, purses and passports.

When people are forced to flee for lives, the belongings they leave behind create an eerie tableau. After the shooting at FLL, about 23,000 items were strewn haphazardly throughout the airport—everything from suitcases and cellphones to baby strollers, purses and passports.

Intent on returning personal effects to their rightful owners, the airport quickly called BMS CAT, a firm that specializes in recovery services for events including airline accidents. The shooting occurred just before 1 p.m, and the company had personnel onsite by 6 p.m.

“As soon as we were off lockdown, they began collecting bags and personal belongings,” says Nonnemacher. The firm worked throughout the night to recover and catalog all abandoned items, which were then stored overnight in a warehouse. The following morning, workers began the arduous task of tracking down owners. “Within one week, we had all but 1,000 items returned,” he remarks.

Nonnemacher learned about BMS CAT at a National Transportation Safety Board Family Assistance Training Forum—an event held several times a year that he highly recommends. “It is really valuable training, and really paid off,” he notes.

Gale urges other airports to identify a company in their area that specializes in this kind of work and establish a contract in advance. “If something goes wrong, you can just pick up the phone and ask them to come,” he says. BMS CAT began operating at FLL under a written emergency work authorization.

Helping customers replace their missing travel documents was another important follow-up effort. The airport worked with the governor’s office to arrange mobile units that issued temporary driver’s licenses and ID cards; and a congresswoman helped secure replacement passports. “We had a lot of international travelers who wouldn’t have been able to get out of the country without the appropriate documentation,” says Gale, again urging other airports to establish connections for assistance in advance.

Recommendation #8: Plan Your Media Response

Before the mass shooting, Meyer and other key personnel in FLL’s Public Information Office had managed two other major news events. In October 2015, 20 people were hospitalized when a Dynamic Airways plane caught fire on a taxiway; and about one year later, the landing gear on a FedEx DC-10 collapsed, causing another aircraft fire.

“In both cases, we had intense media response to what was happening at the airport, and we tried to manage the messaging as much as possible with timely accurate information,” explains Meyer. “For Jan. 6, you could take those two previous events, combine them, and then double that, and I don’t think you would have had the same media response. We had media vehicles triple-parked from Terminal 1 to Terminal 2.”

Meyer’s primary recommendation to other public information officers? Know your craft and be aware of what information the media will seek. “Give them information as quickly and as accurately as possible, and work with your executive team to get them talking to the media,” he advises. “It’s really about transparency and responsiveness and just trying to understand their needs.”

The airport held three press conferences the evening of the shooting, with participation from the sheriff, FLL’s chief executive, an FBI official and the governor. “They were all seasoned professionals, so they knew how to relay the message,” he recalls. “They coordinated behind the scenes about who would speak first and how the event would progress.”

Meyer also recommends calling for backup immediately. Within five minutes of the shooting incident, he reached out to a colleague and asked him to activate the region’s Mobile Joint Information Center, a 30-foot trailer loaded with communications tools, satellite TV, fax machines and computers. A team of 12 public information officers from other organizations worked from the mobile unit, helping the airport team communicate with the EOC and answering calls from the media.

It’s important to answer all calls from the media, notes Meyer. “I started with the local media who were on the property, then I handed my phone over to a fellow public information officer, gave him my password, and asked him to answer each one of my messages,” he relates. “I dealt with the locals first, because I had a personal relationship with them; and then continued with the national correspondents I knew.”

Finally, Meyer advises establishing a specific place for media to gather. The designated media area at FLL is between terminals 1 and 2, with signage directing reporters and camera crews to the right spot. Because FLL had pre-established a meeting area, members of the media weren’t roaming the rest of the airport, he explains.

“This is a place they go to every time they come, whether it’s a single reporter or a group,” Meyer explains. “It is where everybody converged, because they knew we would host news conferences there. We also have a secondary location for large media responses. That’s something I encourage all airports to have, because you never know what kind of event you will have and what the media response will be.”

Recommendation #9: Hold Active Shooter Drills

Nonnemacher firmly believes in the value of running emergency simulations. “We are not resting on our laurels because we had an active shooter event,” he remarks.

In fact, FLL has a drill scheduled in late April to test some of its new processes and systems. The airport plans to simulate an active shooter incident from midnight to 4 a.m. away from public areas. The event is designed to address four main objectives identified in the report that Ross & Baruzzi produced after last year’s shooting. Nonnemacher prefers not to share specific details about the four objectives, but indicates that the simulation will test elements such as new communication strategies and a unified command system. Drill participants will include law enforcement officers, fire/rescue personnel, airport first responders and representatives from airlines, concessionaires and other airport groups.

“Our intent is to drill it and document it, so we can use it as a tool for ourselves and others,” says Gale. “The federal government requires airports to hold a mass casualty exercise for situations like a plane crash every three years. Like many airports, we do this more frequently. But I think it’s time we layer in other types of security exercises. We’ve already done a number of active shooter tabletop exercises, but when you actually role play an event like this, it gives first responders a sense of realism and a better idea of how to deal with these situations.”

Despite the increased training and other improvements that have already been implemented at FLL, some scars from the 2017 mass shooting it experienced will likely be permanent. “Just because we are better prepared, doesn’t mean that everything’s going to be fine,” Gale reflects. “If the same kind of event were to happen again tomorrow, next week, next month or next year, we could wind up with similar outcomes. But we believe through regular meetings with law enforcement and fire/rescue, and by drilling together, at least a piece of how we respond might be much different and much better.

“I’m not faulting anything anybody did on Jan. 6, because it was unthinkable; and everyone acted very heroically. But we still should plan and prepare.”

Update: The accused shooter, Esteban Santiago, is scheduled for trial in June. As of mid-March, prosecutors had not announced whether they would seek the death penalty.

facts&figures

facts&figures