Environmental cleanups at airports often involve old underground fuel tanks, errant deicing fluid or chemical contamination from firefighting foam. At Kingman Municipal Airport (IGM) in northwest Arizona, the issue was toxic aluminum dross.

Never heard of aluminum dross? You’re not alone.

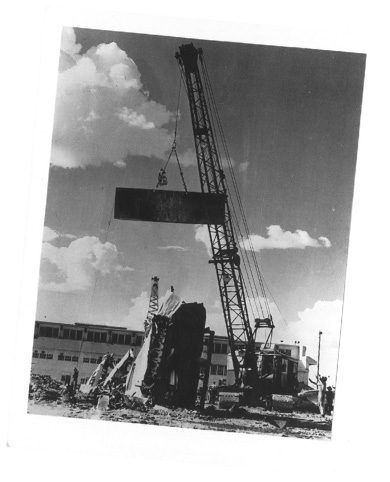

In this case, the dross was a byproduct of the process used to recycle aluminum from obsolete military aircraft. After World War II, thousands of surplus planes were sent to IGM, then known as Kingman Army Air Field. Throughout the mid- to late-1940s, thousands were sold to the public, and some B-17 bombers were even repurposed to spread pesticides to fight a fire ant invasion in the southwest part of the country.

| facts&figures

Project: Excavating & Removing Toxic Waste Location: Kingman Municipal Airport, in AZ Source of Contamination: Dross containing cadmium & lead from melting obsolete military aircraft to recover aluminum content Project Cost: $43.5 million, plus $9 million set aside for contingencies Funding: $52.5 million settlement from lawsuit with federal government (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers hired contractor that buried the waste) Waste Removed: 96,000 tons Timeline: Initial settlement reached in 2016; request for excavation & removal proposals issued Dec. 2021; investigation & design contract awarded to Haley & Aldrich May 2022; final settlement approved by city March 2023; excavation began Sept. 2023; cleanup complete May 2024 Design Build Contractor: Haley & Aldrich Construction Services Engineer: C&S Engineers Hazardous Waste Transport & Disposal: Clean Harbors Key Benefits: New, improved apron free of broken pavement from buried toxic waste |

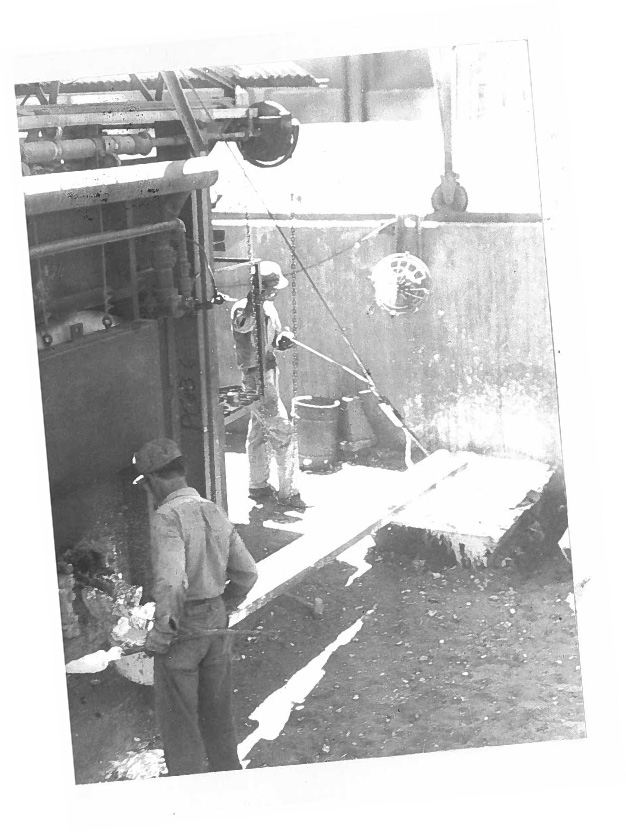

Most of the aircraft, however, were melted down on the south side of the airfield to recover their aluminum content. That process left behind a grayish dross material with toxic levels of cadmium and lead. In the early 2000s, the dross was buried under an asphalt cap by a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers contractor, and then paved over to create an aircraft ramp.

Eventually, the dross pit was compromised by heavy summer rains. This activated the buried material, creating heat and toxic, flammable gases that pressed against the asphalt above like a heavy Thanksgiving meal pushes on one’s waistband.

“The ground in that area of the airport was lifting like a giant volcano,” says Doug Breckenridge, who took the reins as general manager at IGM in 2021. “It was creating FOD [foreign object debris] hazard for our tenants’ aircraft. Our tenants are the heart and soul of this community, and we knew we had to do something.”

Over time, roughly 15 acres of the airfield became unusable as the underground dross continued to crack and fracture the pavement. Finding a solution became a top priority for Breckenridge and his staff. The contaminants were eventually removed and a new apron was created—more than a decade after the issue emerged. (See timeline in the Facts and Figures section to on Page 76 for more details.)

Analyzing the Problem

During World War II, the air field was one of the largest U.S. training bases for aerial gunners. Today, IGM has two active runways and about 150 general aviation operators and/or individual aircraft owners.

“We are a general aviation airport, but we’re more on the industrial side,” Breckenridge explains. “We have aircraft painting facilities for private and regional jets, hangar storage and an aircraft composite repair station on site, along with aircraft upholstery and a small maintenance, repair and overhaul facility. Across the street is a Goodyear aircraft tire refurbishing shop.”

As the deteriorating asphalt situation became untenable for IGM tenants, the city of Kingman hired law firm of Gust Rosenfeld. The city filed a lawsuit against the federal government for not properly handling the dross burial, and Rosenfeld tapped environmental and geotechnical engineering consulting company Haley & Aldrich to assess the challenges it created.

“The eastern part of the site had a lot of heaves under the asphalt,” says Haley & Aldrich engineer Pejman Eshraghi. “Some were 4 to 5 feet in diameter and a foot high; some were 40 feet wide and 3 to 4 feet high. There were also cracks in the asphalt—thousands of them.”

The firm’s environmental experts drilled more than 150 borings, collecting soil samples to better understand the problem and its impact. The project team even developed a new apparatus and used it in tandem with a method developed by the University of Illinois two years earlier to measure and extract gases.

“In the process of creating this heat and the gases, the dross also generated hydrogen and ammonia, which are flammable and toxic,” Eshraghi explains. “This science project should never have been growing underneath an airport.”

Not surprisingly, the presence of buried dross discouraged existing and prospective tenants from wanting to spend time or money at the airport.

After Eshraghi and his team determined the extent of the contamination, they presented a plan to excavate and dispose of the toxic dross.

Obsolete military aircraft were chopped up and melted down for their aluminum content.

Funding and Implementing the Fix

The city had a strong case for its lawsuit, based on the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, which established prohibitions and requirements concerning closed and abandoned hazardous waste sites.

The city had a strong case for its lawsuit, based on the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, which established prohibitions and requirements concerning closed and abandoned hazardous waste sites.

The city council approved a partial settlement for $52.5 million in March of 2023, and IGM gave Haley & Aldrich the green light to move forward. The airport and consultant agreed to a project that would cost $43 million, with $9 million set aside for continencies.

Over a span of nine months, Haley & Aldrich removed 96,000 tons of toxic material from the dross pit and transported it off-site to be disposed of as hazardous waste. Breckenridge describes the operation as a surgical process, with workers excavating up to 20 feet deep until no more dross was found. It was like digging out cancerous cells from under the skin of the airfield pavement.

These days, the airport stores hundreds of civilian aircraft. Most are commercial airliners maintained to remain in airworthy condition.

To get the waste out of Arizona, Haley & Aldrich engaged Clean Harbors to transport the material to its hazardous waste disposal facility in Oklahoma.

“At first, we thought we’d have to ship the dross up Highway 93 to Beatty, NV, through Las Vegas,” Breckenridge says. “But at the request of City Council to use rail in order to reduce traffic, noise and air pollution, Haley & Aldrich and Clean Harbors came up with the plan to use Patriot Rail’s newly constructed transload facility within Kingman Airport and Industrial Park. We discovered we could put it on a train heading directly east instead of trucking it through multiple cities.”

In all, the toxic materials filled about 924 railcars—a strategy Haley & Aldrich says saved the airport about $2 million in disposal costs compared to transporting it in trucks. The environmental firm also found a way to process and reuse the asphalt cap, which eliminated other disposal costs.

Impact on Tenants

Reclamation work was completed in phases to limit disruptions to airport operations. Afterward, IGM had a repaved, fully functional apron.

“The big takeaway was how to work with an active airport,” Eshraghi states. “A lot of planes were using this apron, and we needed to dig everything in an orderly fashion, phase by phase, while making sure the tenants were not impeded due to construction.”

“The big takeaway was how to work with an active airport,” Eshraghi states. “A lot of planes were using this apron, and we needed to dig everything in an orderly fashion, phase by phase, while making sure the tenants were not impeded due to construction.”

One such tenant is Alpha-Zulu Composites, a composite aircraft repair facility. Owner Paul Gaines was alarmed at the first official meeting with the airport when he learned the project would take almost a year.

“I was taken aback,” Gaines recalls. “But I knew the old dross material had to be removed and the existing surface was terrible for aircraft operations. It became much easier to process and absorb when it became obvious how much the airport cared about our operations and how well they listened as things progressed.”

The airport shared plans for the project with Gaines and other tenants, taking time to understand their needs. Contractors, in turn, remained flexible as work progressed. Ultimately, Alpha-Zulu’s daily operations weren’t affected and the company continued receiving and delivering aircraft as needed.

“We now have a beautiful ramp area with a renewed infrastructure,” Gaines reports. “It’s so very critical for existing and future businesses.”