The recent addition of an upgraded air traffic control tower has given Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport (AZA) an inside track to welcoming more passengers while supporting a surge in aviation-related commercial development. Last August, AZA activated its John S. McCain III Air Traffic Control Tower, a nearly 200-foot-tall, $30 million addition that immediately improved airfield safety and boosted operational capacity at the expanding reliever airport.

The recent addition of an upgraded air traffic control tower has given Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport (AZA) an inside track to welcoming more passengers while supporting a surge in aviation-related commercial development. Last August, AZA activated its John S. McCain III Air Traffic Control Tower, a nearly 200-foot-tall, $30 million addition that immediately improved airfield safety and boosted operational capacity at the expanding reliever airport.

“This is infrastructure that we critically needed to be able to continue to meet the changing air transportation needs in greater Phoenix,” explains J. Brian O’Neill A.A.E., executive director/chief executive officer of the Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport Authority. “We were an airport that had outgrown the 1970’s military base tower that was left after Williams Air Force Base had closed.”

“This is infrastructure that we critically needed to be able to continue to meet the changing air transportation needs in greater Phoenix,” explains J. Brian O’Neill A.A.E., executive director/chief executive officer of the Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport Authority. “We were an airport that had outgrown the 1970’s military base tower that was left after Williams Air Force Base had closed.”

Located about 20 miles southeast of Sky Harbor International (PHX)—a perennial Top 10 large U.S. hub—AZA has carved a niche for itself as an active general aviation field with a diverse array of leisure-oriented airlines. In 2022, the airport served 1.9 million passengers, with nonstop commercial service to more than 50 markets across the U.S. and Canada.

|

Project: New Air Traffic Control Tower Location: Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport Height: 200 ft. Size of Cab: 550 sq. ft. Cost: $30 million Funding: $28 million from FAA; $2 million airport funds Design: Leo A. Daly Construction Manager at Risk: DPR Construction Project Timeline: 3 yrs from design through construction Tower Activated: Aug. 2022 Digital Platform: Frequentis USA Airfield: 3 parallel runways; 260,038 flight operations in 2022 Traffic Profile: Active general aviation customer base; commercial service by Allegiant; Flair; Sun Country; Swoop; WestJet Key Benefits: Taller tower provides view of entire airfield; larger cabin with updated technology improves controllers’ workspace Noteworthy Detail: Airport rallied congressional support to eliminate provisions that restricted federal funding for airport-owned contract towers as part of the 2018 FAA Reauthorization Bill. |

AZA achieved these milestones despite decades of limitations presented by its old control tower, which was originally built to support military flight training. The cab lacked sufficient space to best manage the airport’s growing flight volume, and the tower itself was too short for controllers to see the entire airfield, which has an unusual configuration of three parallel runways.

For years, airport management sought in vain for FAA approval to build a new tower. Ultimately, it took the demise of an archaic federal regulation for the project to move forward. With that obstacle finally cleared four years ago, AZA built a modern tower and fast-tracked additional capital improvements to accommodate more commercial flights. In addition, more than 1 million square feet of private development is rising from the fallow desert just east of AZA’s airfield.

“Our new air traffic control tower is going to serve as a catalyst for continued development,” says O’Neill. “Without it, our older tower would have been a governor on what we’ll be able to achieve.”

Change Agents

The antiquated nature of AZA’s former tower was never in question. At 120 feet, it wasn’t tall enough to meet controllers’ visual needs, and its 225-square-foot cab was only half the size of its eventual replacement. Beyond cramped quarters that leaked during rare desert rainstorms, O’Neill jokes that controllers enjoyed “free workouts” when the elevator was inoperable – which was often.

With recreational pilots, flight schools, itinerant military aircraft and steady commercial and cargo operations, AZA is one of the busiest U.S. airports for movements. But even that status was initially not enough to overcome regulations limiting federal contributions for replacing its specific type of tower, which is airport-owned but operated by contract controllers.

Four decades ago, leaders in Washington established the Federal Contract Tower program, enabling private employees to direct aircraft movements on a contract basis in lieu of FAA-hired air traffic controllers. But with that flexibility came a large chunk of red tape—specifically, a $2 million hard cap on Airport Improvement Program (AIP) contributions toward construction of airport-owned contract towers. The AIP cap also applied to discretionary funding, so even if a contract tower airport could qualify for enough AIP dollars to pay for its own replacement tower, the law still prevented spending more than $2 million in federally provided funds over the life of such projects.

Efforts to overturn that regulation began at AZA nearly a decade ago. O’Neill credits his predecessor, former Executive Director Jane Morris, for initiating the push that eventually ended the cap.

Morris felt that the solution was to go to Washington and change the federal law—a strategy that originally sounded “a little bit far-fetched” to O’Neill. But Mesa’s mayor bought in, and soon a lobbying team was formed. One early win involved inviting then-U.S. Sen. John McCain for an airport tour.

“At the end, he looked us in the eye and said, ‘You need a new tower,’” O’Neill recalls. Although McCain died just weeks before the cap was lifted, his efforts inspired other Arizona lawmakers. Support came from both sides of the political aisle, including U.S. Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, an Independent who was previously a Democrat U.S. House member; and U.S. Rep Andy Biggs, a Republican now representing Arizona’s 5th District.

“At first, I was skeptical,” Biggs says. “[The government is] spending all kinds of money on goofy projects. We’ve got a project here and we can’t spend any money on it, even though a good portion of the money was there? It seemed absolutely irrational to me.”

After researching the matter, Biggs recognized AZA’s challenge was indeed real. So he and his colleagues went to work to make changes. “Everyone in the delegation was all-in on this,” he recalls.

The $2 million cap was removed as part of the FAA Reauthorization Bill passed in October 2018. Two years later, Rep. Greg Stanton, a Democrat from Arizona’s 4th Congressional District, helped secure $10 million in FAA discretionary grants to fund AZA’s new tower. In a press release issued at the time, Stanton said it was critical for the airport to keep pace with the region’s growth. He also praised the FAA saying, “Delivering on this commitment is a win for the East Valley and for the entire Phoenix region.”

AZA eventually received roughly $28 million in federal support for the tower replacement. Like Stanton, O’Neill credits the FAA for its collaborative partnership, and specifically cites the Phoenix Airport District Office and the Western-Pacific Region. He also notes that AZA’s successful push to eliminate the $2 million cap will help other small airports with contract towers pursue funding for needed infrastructure improvements.

“The FAA was with us every step of the way to make sure what we were building, what we were planning to build, was sufficient—what we needed, not what we wanted,” O’Neill specifies. “If there’s a fit, a need and an ability to make it happen, possibly others will benefit from the hard work [accomplished] during our process.”

Beyond that, Biggs notes that adding capacity at AZA and other relievers benefits an increasingly congested National Airspace System. “Not only are we relieving from the Phoenix metro area, but even in some instances from (airports in) Southern California,” he explains.

Ironically, AZA’s recent successes could lead to its graduation from a contract tower to an FAA-managed facility. With an eye to the future, the airport built the McCain Tower to FAA specifications, and given the current volume and growth potential, airport leaders have already approached the federal agency to inquire about what might trigger such a change. Although there is no such precedent nor associated procedures in place, AZA leaders would prefer to see FAA controllers taking over for contracted employees in the coming years.

Threading a 200,000-Pound Needle

Beyond gaining FAA funding and approval, building the tower was not without challenges. Bob Draper, director of Engineering and Facilities at AZA, approached the project with a simple goal: “The first thing I told everyone was, ‘I want to be in the news for this project, but for the right reasons. Not because we skimped on safety, and not because we didn’t do our due diligence and wasted millions of dollars.’”

An industry veteran with more than 30 years’ experience on airport and highway jobs, Draper appointed himself project manager and welcomed the opportunity to build a tower. His excitement is evident when he describes the foundation’s 37 caissons, each 80-feet deep and topped with 6 feet of concrete and thick strands of rebar. “And that was before we ever started coming out of the ground,” Draper says. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

An industry veteran with more than 30 years’ experience on airport and highway jobs, Draper appointed himself project manager and welcomed the opportunity to build a tower. His excitement is evident when he describes the foundation’s 37 caissons, each 80-feet deep and topped with 6 feet of concrete and thick strands of rebar. “And that was before we ever started coming out of the ground,” Draper says. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

DPR Construction won a competitive bidding process and was tasked with building the tower. Its team oversaw onsite fabrication of two steel structures: a 110,000-pound controller cabin and a 206,000-pound lower “bulge” that houses a break room and office, meeting space and restrooms. At its peak, the project included 85 full-time construction workers. Overall, more than 30 subcontractors took part in developing the tower.

“This was taking something as complex as a data center and everything that would go into it from an infrastructure standpoint, and then trying to build it vertically,” says Geoffrey Minor, a senior project manager at DPR Construction’s Phoenix office.

For Minor and his crew, the most stressful portion came near the end, when a crane lifted the two steel structures into place atop the 120-foot-tall base tower. Workers had to fit the massive pieces above and around a 30-foot-tall precast elevator shaft, with just 1 inch of clearance on three sides. Before the heavy pieces were lifted, quality control agents used laser scanning, models and other detailed methods to verify that each piece would properly align.

“The precision required to get that to slide right down over (the shaft) made everything more challenging,” Minor says. “Having folks 150 feet up in the air guiding this in; a crane operator trying to maneuver this in; making sure the anchor bolts all lined up and it slid right into place…that’s a memory I’ll never forget.”

“The precision required to get that to slide right down over (the shaft) made everything more challenging,” Minor says. “Having folks 150 feet up in the air guiding this in; a crane operator trying to maneuver this in; making sure the anchor bolts all lined up and it slid right into place…that’s a memory I’ll never forget.”

The lifts occurred over a six-day span in August 2021. Draper likened the process to threading a massive needle. “There was an extreme amount of nervousness and tension,” he recalls. “Every little piece had to work together. When it was finished, I went and laid down. It was like finishing a big race or sporting event.”

The project was executed under a construction manager at risk agreement, and major subcontractors tailored their designs onsite, which helped workers more easily match pre-cast concrete base pieces with structural steel. From design to completion, the project took three years and finished on budget and on schedule. Draper notes that the team’s focus on precision paid off. “The final photos are so close to the original renderings, you can hardly tell the difference,” he remarks.

Improvements inside the cab are also noteworthy. Frequentis USA, a Maryland-based communications firm, outfitted the tower with an integrated digital platform the company describes as the nation’s first controller-to-pilot IP voice communication setup. To improve controller efficiency, the system features integrated recording tools, plus digital terminal information and weather services.

With the new tower online, AZA narrowly missed ranking as the nation’s busiest federal contract tower in FAA’s 2022 fiscal year, which ended Sept. 30. The airport’s 260,038 operations were only 267 fewer than the year-end total of top-ranked North Perry Airport (HWO) in Broward County, FL.

Still, less than 5% of AZA’s operations involve commercial operations. Its 10 gates have historically been most active in mornings and late evenings, due to primary tenant Allegiant Air’s practice of starting and ending crewmembers’ days at their origin bases. But recently, it and other carriers have begun scheduling more midday, afternoon and early evening flights, somewhat leveling out the operational peaks.

Looking ahead, O’Neill is far from content. He hopes to augment AZA’s current leisure-heavy schedule with select business routes to western hubs operated by network carriers.

“We have done a good job of proving to the airlines that this is a market that is outside the shadow of Phoenix Sky Harbor, and it’s a market we think they’ll be successful serving,” he says. “If you get a reliable, daily business product—for example, United to Denver and beyond—then you could get the growing number of business travelers who live in the East Valley to fly out of this airport and avoid having to go to PHX. We have a real opportunity to take this airport to the next level.”

|

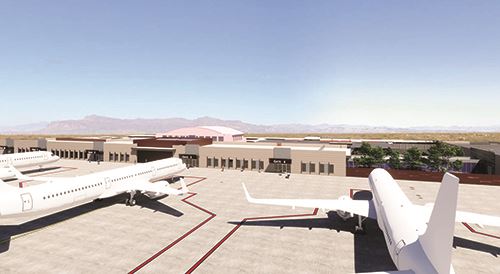

From Military Base to Boomtown A new control tower is just the tip of the iceberg at Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport (AZA). Other significant improvements include a new $28 million terminal concourse that just started construction and a flurry of private development backed by notable aviation giants. Like many U.S. airports, AZA started off as a mid-century military installation. The U.S. Army Air Corps opened an Advanced Flying School outside Phoenix in July 1941, just months before the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor thrust the United States into World War II. With wartime demand for pilots skyrocketing almost overnight, activity at the nascent airfield quickly took off. The site was named Williams Field in February 1942 to posthumously honor Charles L. Williams, an Arizona-born military pilot. Post-war it was again renamed, this time as Williams Air Force Base in 1948. From wartime through its 1993 closure, more than 26,500 military fliers completed their pilot training there. In 1994, the facility began its second life as a public airport—initially as Williams Gateway, and later as Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport when commercial service was added in 2007. The following year, AZA opened a 10,000-square-foot modular terminal to temporarily house four commercial gates. Permanent gate facilities arrived in 2010, 2012 and 2014. Today, the growing airport has 10 ramp-loaded gates. AZA served just 237,039 passengers during its first 12 months of commercial operation, but a surge in traffic developed along with terminal additions as Phoenix-area residents and visitors responded to the conveniences of the small commercial airport. Annual traffic has grown steadily in recent years, thanks to a mix of low-cost domestic flights from Allegiant Air, Sun Country Airlines and, for a time, Frontier and Spirit airlines—coupled with a steady stream of snowbird-filled Canadian routes from Flair Airlines, Swoop and WestJet. In calendar year 2022, AZA exceeded 1.9 million passengers– its best annual total to date. Airport officials project similar volume for 2023.

While COVID-19 brought new challenges and temporarily slowed the airport’s ascent, the pandemic also fueled opportunities for expansion. Rigid social distancing requirements forced AZA to use only two of the modular terminal building’s four gates during parts of 2020 and 2021. But once growth resumed in earnest, airport leadership moved quickly to address AZA’s spatial shortcomings with a $14.8 million federal grant awarded under the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. That funding was a catalyst for a new 30,000-foot, five-gate terminal modernization project that recently broke ground to replace the airport’s original four-gate modular terminal. The $28 million project is expected to be finished in first quarter 2024, and will mark the end of capital improvements on AZA’s west side. Long-term plans call for a new terminal campus east of the airfield, though airport leaders say initial work on that development is likely more than a decade away. For now, it’s the private sector that is making major improvements along the airport’s eastern perimeter. SkyBridge Arizona, a 360-acre multi-use project, has leased a nearly 60,000-square-foot hangar to Gulfstream Aerospace and is developing the first air cargo hub to offer joint U.S./Mexican Customs inspection facilities. Separately, Virgin Galactic is building hangars to assemble its “Mothership” and associated spacecraft for forthcoming commercial space service. Another nearby master development, Gateway East, will house non-aeronautical businesses and air service support providers across a 300-acre site adjacent to AZA and two major Arizona highways. “What we have that Sky Harbor does not is a significant amount of land adjacent to our three 10,000-foot-long runways,” explains J. Brian O’Neill A.A.E., executive director/chief executive officer of the Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport Authority. “We’re never going to be a hub for American Airlines or a focus city for Southwest Airlines. But you’re going to see other aviation-related companies come here, joining Virgin Galactic, Gulfstream, Cessna and Embraer in calling Gateway Airport home … As we continue to grow that, the trickle-down economic sustainability for the entire region is incredible.” These days, AZA contributes more than $1.8 billion annually to the regional economy. And O’Neill says that none of the airport’s recent or projected growth would be possible without the new tower and other infrastructure investments. |