In a world where many people navigate life with their heads down and eyes trained on their own cellphones, George Bush Intercontinental Airport (IAH) is prompting visitors in Terminal E to look up for a shared digital experience called the Oculus. An enormous ring of light and multimedia motion that hovers between the ticketing and baggage claim levels in the new International Central Processor encourages visitors to stop and watch sweeping waves of color and graphics. Those who are really paying attention may notice that the visual presentation responds to their movement; however, few will consider the years of planning, coordination and experimentation that made IAH’s new landmark possible.

Leaders at Houston Airports emphasize that the stunning display unveiled in fall 2025 and other digital systems such as self-service processing kiosks are more than new infrastructure. “The new international terminal at George Bush Intercontinental Airport (IAH) represents the future of global air travel—where technology, efficiency and design come together to create a seamless passenger experience,” remarks Director Jim Szczesniak. “The new IAH International Central Processor will be a centerpiece of that experience. Its architecture and immersive digital design will form a beautiful jewel box that delights and inspires wonder from both levels.”

Leaders at Houston Airports emphasize that the stunning display unveiled in fall 2025 and other digital systems such as self-service processing kiosks are more than new infrastructure. “The new international terminal at George Bush Intercontinental Airport (IAH) represents the future of global air travel—where technology, efficiency and design come together to create a seamless passenger experience,” remarks Director Jim Szczesniak. “The new IAH International Central Processor will be a centerpiece of that experience. Its architecture and immersive digital design will form a beautiful jewel box that delights and inspires wonder from both levels.”

What appears to be a single, continuous display is actually an intricate orchestration of architecture, electronics, software and creative content designed to welcome visitors and celebrate the city itself. “This is about connecting Houston to the world and the world to Houston in a way that drives economic growth and reflects the innovation that defines our city,” Szczesniak notes.

facts&figuresProject: Digital Video DisplayLocation: George Bush Intercontinental, in Houston Name: The Oculus Size: 93 ft. × 16 ft.; 226.5 ft. linear span; about 1,955 sq. ft. of active LED surface Resolution: 34,584 × 1,416 pixels (about 49 million total) Planning, Design & Construction: 2021–2025 Key Components: Real-time interactivity via dual LIDAR sensors; 6 synchronized video playback servers; dynamic brightness & content scheduling; integrated generative Unreal Engine content Technology Integrator: Ford Audio-Video Systems Owner’s Authorized Representative: Burns Engineering Architectural Designer: HOK Creative Design & Content Production: Gentilhomme LED Manufacturer: Nanolumens Content Management & Playback Systems: Smart Monkeys; AV Stumpfl Pixera Monitoring & Control: Smart Monkeys ISSAC / Nanolumens NanoSuite / Pixera media players Key Benefits: Enhances passenger experience; celebrates Houston’s identity; supports terminal flow; accessible to general public |

To help bring the Oculus to life, Houston Airports hired Burns Engineering as its Owner’s Authorized Representative. While Burns provided technical oversight from early planning through final commissioning, Nanolumens engineered and manufactured the custom LED display. Ford Audio-Video Systems (Ford AV) managed the complex systems integration and coordinated the technology that drives the array, and Gentilhomme Studio led creative design and content production.

From Concept to Reality

When Houston Airports first explored adding a large-scale digital feature at IAH, the goal extended beyond simple aesthetics. The team wanted to create an experience that would connect travelers to the identity of Houston in a way that felt seamless. “The earliest discussions focused on their vision for the digital experience so we could understand how to bring and maintain stakeholder involvement through the multi-year process,” recalls Matthew Meier, project manager with Burns Engineering.

In addition to coordinating project designers, engineers and creative teams, the firm also validated the structural design from HOK: a cantilevered, angled fascia strong enough to support the massive media system yet still integrate into the terminal’s clean existing architectural lines. Burns personnel worked closely with HOK’s architectural team and Nanolumens’ engineering specialists to confirm load paths, materials and attachment points that balanced strength with the architectural effect envisioned by Houston Airports.

Although travelers might think IAH’s new digital display is just another big, splashy LED wall, it is significantly different from most. Unlike flat or cylindrical displays common in sports stadiums and arenas, the Oculus is a tilted oval that is narrower at the top than the base—like a truncated cone. “The most complex part is it’s actually tilted down,” explains Mitch Warren, senior design engineer with Ford AV. “The video surface is not perpendicular to the floor.”

The distinct shape and geometry include continuous curves along multiple axes, which presented considerable challenges for project partners. “Nanolumens had to custom manufacture all these trapezoidal LED panels that don’t exist anywhere else in the world,” Warren notes. No two panels are identical, but together, they form a structure that provides a truly unique visual experience.

In fact, the Special Projects Group at Nanolumens spent years developing the technical framework that made the display possible. “Nanolumens’ R&D and Mechanical Engineering teams worked to develop the custom componentry required to match the design intent,” explains Todd Alan Green, the company’s global director of Airports and Transportation.

Due to the complexity, Nanolumens designed both the video surface and its supporting mount as a unified system with a frame to match precisely with the terminal’s steel and structure. “It really had to be exact,” Warren notes. With such tight tolerance requirements, crews had to make small, precise adjustments—working just a few feet at a time—continuing this process until the entire perimeter was aligned.

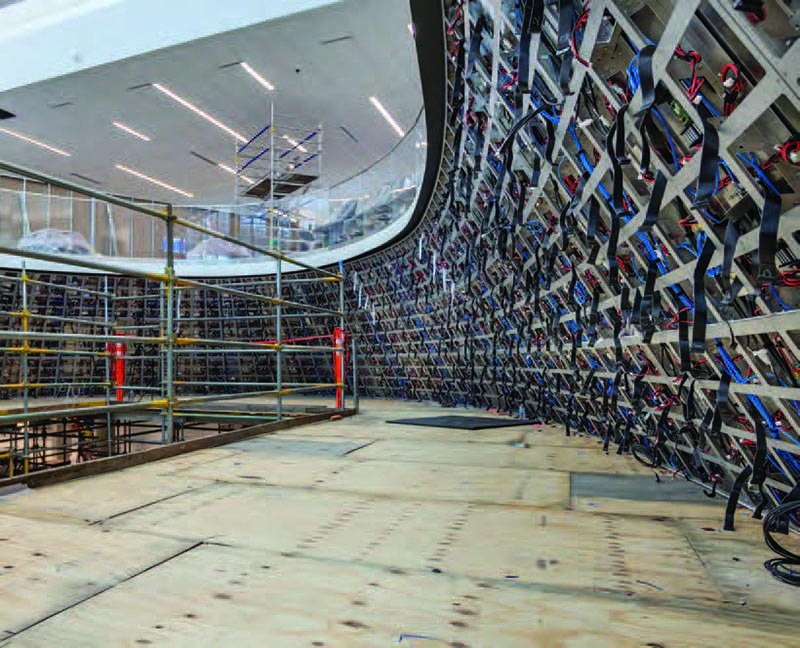

Each of those adjustments supported an underlying design that was entirely custom. The Oculus consists of eight distinct arc sections built from 36 types of custom polygonal LED tiles. “In total, Nanolumens created nine unique Nixel Series LED frame shapes and fabricated 84 discrete LED frames to achieve the continuous, sculptural form of the Oculus,” explains Dan Rossborough, director of the Special Projects Group with Nanolumens.

Each of those adjustments supported an underlying design that was entirely custom. The Oculus consists of eight distinct arc sections built from 36 types of custom polygonal LED tiles. “In total, Nanolumens created nine unique Nixel Series LED frame shapes and fabricated 84 discrete LED frames to achieve the continuous, sculptural form of the Oculus,” explains Dan Rossborough, director of the Special Projects Group with Nanolumens.

Long-term durability was a core design requirement, and the system includes both passive and active cooling for stable operation in Houston’s hot, humid climate. “Nanolumens’ modular Nixel system allows for front-serviceable access, meaning individual panels can be replaced or serviced without disrupting the surrounding structure,” says Green. “Combined with remote system monitoring through NanoSuite, this design ensures minimal downtime and proactive maintenance.”

Measuring 93 feet long and 16 feet tall, the Oculus spans more than 226 linear feet with a surface area of roughly 1,955 square feet and a resolution of 34,584 by 1,416 pixels—nearly 49 million in total. “The pixel pitch ranges from 2.0 millimeters to 1.4 millimeters, enabling exceptionally high visual detail,” says Green.

Measuring 93 feet long and 16 feet tall, the Oculus spans more than 226 linear feet with a surface area of roughly 1,955 square feet and a resolution of 34,584 by 1,416 pixels—nearly 49 million in total. “The pixel pitch ranges from 2.0 millimeters to 1.4 millimeters, enabling exceptionally high visual detail,” says Green.

Early plans called for 4K video, but as the design advanced, engineers realized that the extreme width and relatively short height of the Oculus required a non-standard resolution. “There were a number of design changes and technical challenges that we had to work through to make that a reality, because most video processing equipment can’t handle non-standard resolutions. So we had to rework the infrastructure,” Warren explains.

Each section of the display connects to an extensive network of cables, redundant control wiring and synchronized video servers.

The environment within the International Central Processor required fine-tuning regarding light and contrast. Though partly sheltered from direct sun, the Oculus sits in a naturally bright area. Light sensors and content variations allow IAH to balance brightness for daytime and evening conditions and keep imagery vibrant but comfortable to the eye.

Building, Testing and Validation

Burns Engineering built multi-stage commissioning into the project plans. “Stepwise, parallel testing was included as part of the procurement process,” Meier explains. “This provided checkpoints to ensure specific display, content management and content elements were tracking and providing feedback with each other.” A highly collaborative process among engineering, integration and creative teams sharing constant feedback helped confirm that system components operated precisely as intended.

Burns Engineering built multi-stage commissioning into the project plans. “Stepwise, parallel testing was included as part of the procurement process,” Meier explains. “This provided checkpoints to ensure specific display, content management and content elements were tracking and providing feedback with each other.” A highly collaborative process among engineering, integration and creative teams sharing constant feedback helped confirm that system components operated precisely as intended.

Prior to installation, every component was prototyped and tested in multiple environments. Gentilhomme used the LED environment in its Montreal studio to fine-tune color calibration and server synchronization, ensuring the content pipeline aligned with the physical display. “The way content is designed affects pixel mapping, the type of servers, synchronization—everything,” explains Gentilhomme Chief Executive Officer and Executive Creative Director Thibaut Duverneix. “People think content is just video, but it’s way more than that. It’s infrastructure, engineering and workflow.”

To validate the design and function before fabrication, Nanolumens constructed a full-scale factory mockup at its headquarters in Georgia. This allowed Houston Airport System, Ford AV and other key project partners to verify visual performance, geometry and structural alignment. Once approved, the mockup was disassembled, shipped and reassembled at Ford AV’s Houston facility for further review—confirming structural fit, color accuracy and display performance well before final assembly.

Each LED tile was then factory-calibrated and color-matched to ensure uniformity across the entire surface. Long-term consistency is managed through the Nanolumens NanoSuite monitoring and management platform, which provides real-time diagnostics, remote oversight and continuous color-uniformity control. The electronics operate through AV Stumpfl’s Pixera media servers and Smart Monkeys’ ISSAC platform, integrated with NanoSuite for scheduling, monitoring and performance management.

Once the structure was set in place at the airport, Ford AV began what the team called “skinning the Oculus”—installing small LED tiles, each roughly one foot square, across nearly 2,000 square feet of surface area, with multiple performance checks throughout the process. “It wasn’t like you finish building and then see if it works,” Warren remarks. “We built a section, tested it, built another, tested again. It was a continuous process to make sure every module, cable and signal path performed exactly as expected.”

Once the structure was set in place at the airport, Ford AV began what the team called “skinning the Oculus”—installing small LED tiles, each roughly one foot square, across nearly 2,000 square feet of surface area, with multiple performance checks throughout the process. “It wasn’t like you finish building and then see if it works,” Warren remarks. “We built a section, tested it, built another, tested again. It was a continuous process to make sure every module, cable and signal path performed exactly as expected.”

Behind the scenes, each section of the display connects to an extensive network with hundreds of power and data cables, redundant control wiring and six synchronized video servers. Any misalignment—even by a fraction of a second—could cause visible seams, so Ford AV coordinated with Nanolumens, Smart Monkeys and AV Stumpfl Pixera to create smooth playback across the entire curved surface.

Once the system was operational, Ford AV, Nanolumens and AV Stumpfl Pixera trained Houston Airports personnel on daily use and scheduling. Because of the system’s sophisticated nature, IAH has a six-year maintenance and support contract with Ford AV for ongoing, preventative maintenance checks and on-call response for technical issues.

Through the Looking Glass

While engineers focused on ensuring the Oculus would function properly, Gentilhomme developed what passengers and the general public would see. “The idea was to create a piece that’s about place-making and identity and part of the architecture, but also to create dynamic content that will adapt to the building and the surrounding conditions,” explains Duverneix, who led the conceptualization, production and integration of visual content.

The studio’s mantra for the project was “Vision is in the air—the Oculus as a looking glass into the past, present and future of Houston.”

Gentilhomme produced 29 original pieces of content, totaling 135 minutes of video. The collection ranges from computer-generated and mixed-media compositions to cinematic live-action scenes. Sequences include artistic murals literally erupting with color, flowing video of local landscapes and images that convey Houston’s pivotal role in space exploration.

Gentilhomme produced 29 original pieces of content, totaling 135 minutes of video. The collection ranges from computer-generated and mixed-media compositions to cinematic live-action scenes. Sequences include artistic murals literally erupting with color, flowing video of local landscapes and images that convey Houston’s pivotal role in space exploration.

Compelling form and content notwithstanding, interactivity is what really sets the Oculus apart from digital installations at other airports. Two LIDAR sensors mounted on opposite sides continuously scan the floor below and generate a live movement tracking of people under the Oculus, including their individual positions and heights. That data drives real-time effects through Unreal Engine, using Pixera’s in-house Unreal plugin, which are then rendered simultaneously across the six Pixera servers.

One of the interactive scenes propels visitors into imagery that looks like a pool of marbles. “As you walk by, you become a giant ball, and that ball pushes the other balls,” Duverneix describes. “It creates this playful physics moment where everybody can engage.” Gentilhomme designers intentionally kept the level of interactivity subtle to prevent crowding or bottlenecks beneath the display.

Other generative scenes respond to local temperature, weather data, seasons and light levels, allowing the display to evolve organically with the current environment. “It’s passive content that is ambient but that’s going to react with external data,” Duverneix explains.

This deep level of customization makes the Oculus truly one of a kind, he emphasizes. “It’s very elegant,” Duverneix adds. “The way it’s been integrated within the architecture works very well. I think it’s going to set a new standard in place making in entertainment and transportation hubs.”

Local Inspiration

The visual content highlights the culture, geography and spirit of Houston. Aerial drone footage captures the downtown skyline in sweeping 360-degree motion. Other sequences explore logistics hubs at the port, birds flocking in the region’s expansive skies, and fields of bluebonnets (the state flower).

Gentilhomme worked with several local artists to create time-lapse video of blank walls being transformed into a colorful mural, ultimately for digital presentation. “That one is kind of interesting because we wanted a one-to-one ratio [with the dimensions of the Oculus],” Duverneix shares. “So, we had to find a place that would be big enough to do that.” Over four days, local artists Anat Ronen, Floyd Mendoza, Jessica Rice, GONZO247, Lee One and the artist named Black created a single continuous mural on the walls of an unused tunnel at the airport. “It was crazy, but it’s a lot of fun,” Duverneix remarks.

To incorporate the performing arts, Gentilhomme collaborated with Vitacca Ballet of Houston. A choreographed performance looks like it occurred in front of the Gerald D. Hines Waterwall, a well-known local fountain. But the project team actually filmed dancers in an extended reality studio and then merged that footage with video of the Waterwall that was shot on location.

Another key sequence pays homage to Houston’s aerospace legacy through computer-generated imagery depicting the evolution of space exploration. That content was created in coordination with NASA.

Public Access

Notably, the Oculus is located on the landside of Terminal E. For Warren, that public exposure is exciting because most of Ford AV’s other airport installations are behind TSA checkpoints, and many of its other complex projects are in private facilities. “Anybody that wants to see and experience the Oculus can just show up,” he says. “You don’t need to spend a bunch of money—you can just show up and come see how cool it is.”

The Oculus is located between the ticketing and baggage claim levels, visible to passengers and the general public.

Because the new display is visible to all arriving and departing passengers as well as the general public, inclusivity was essential. Duverneix notes that content was intentionally designed to avoid quick flickers or abrupt cuts that could trigger those with photosensitivity. “When you treat content as a piece of architecture, you’re trying to make people forget or not even recognize that it’s a screen,” he says.

Content was also designed with slow, fluid motion to suit the Oculus’ large scale and prevent motion sickness or disorientation for viewers moving beneath the low, curved structure. The LIDAR system was arranged to recognize people of varying heights, including those in wheelchairs, so all visitors can enjoy the interactive elements.

A Learning Experience

Although Nanolumens has delivered many custom and architecturally integrated LED systems throughout the world, Green considers the one at IAH among the firm’s most distinctive installations. “Only a few projects share the geometric and engineering sophistication of the Oculus,” he remarks.

Not surprisingly, Green counsels airports considering similar installations to engage promptly with their display manufacturer during design and planning. “Early collaboration ensures that structural, power and content requirements are properly integrated into the architectural concept,” he says. “Mockups and proof-of-concept testing are invaluable for aligning expectations and validating designs before fabrication.”

Not surprisingly, Green counsels airports considering similar installations to engage promptly with their display manufacturer during design and planning. “Early collaboration ensures that structural, power and content requirements are properly integrated into the architectural concept,” he says. “Mockups and proof-of-concept testing are invaluable for aligning expectations and validating designs before fabrication.”

As part of the owner’s representative leadership, Meier says the success at IAH hinged on maintaining focus and vision from the very beginning. “Start by thinking big and creating a strong vision,” he advises. “There are bound to be various challenges in any large terminal project, let alone one with an intricate immersive display feature seamlessly integrated between two floors.”

Meier also credits consistent engagement and collaboration from Houston Airports throughout the multi-year effort. “Their dedication and commitment were crucial for the successful execution of the Oculus,” he notes.

Ford AV’s Warren emphasizes the importance of thorough long-range planning. “With a project this size and this complex, everybody that was involved learned a lot,” he remarks. “It literally took a complete team of subject matter experts from many different disciplines all working together as one cohesive unit to make it happen.”

Duverneix, from Gentilhomme, says the process used to create the Oculus can provide a model for other airports. “The mistake is to start those projects from an infrastructure point of view,” he cautions. “You have to start with a vision. People might think that content is paint—‘We build it, and at the end we put some content in it.’ Content is not paint. It is the project. You have to start there.”