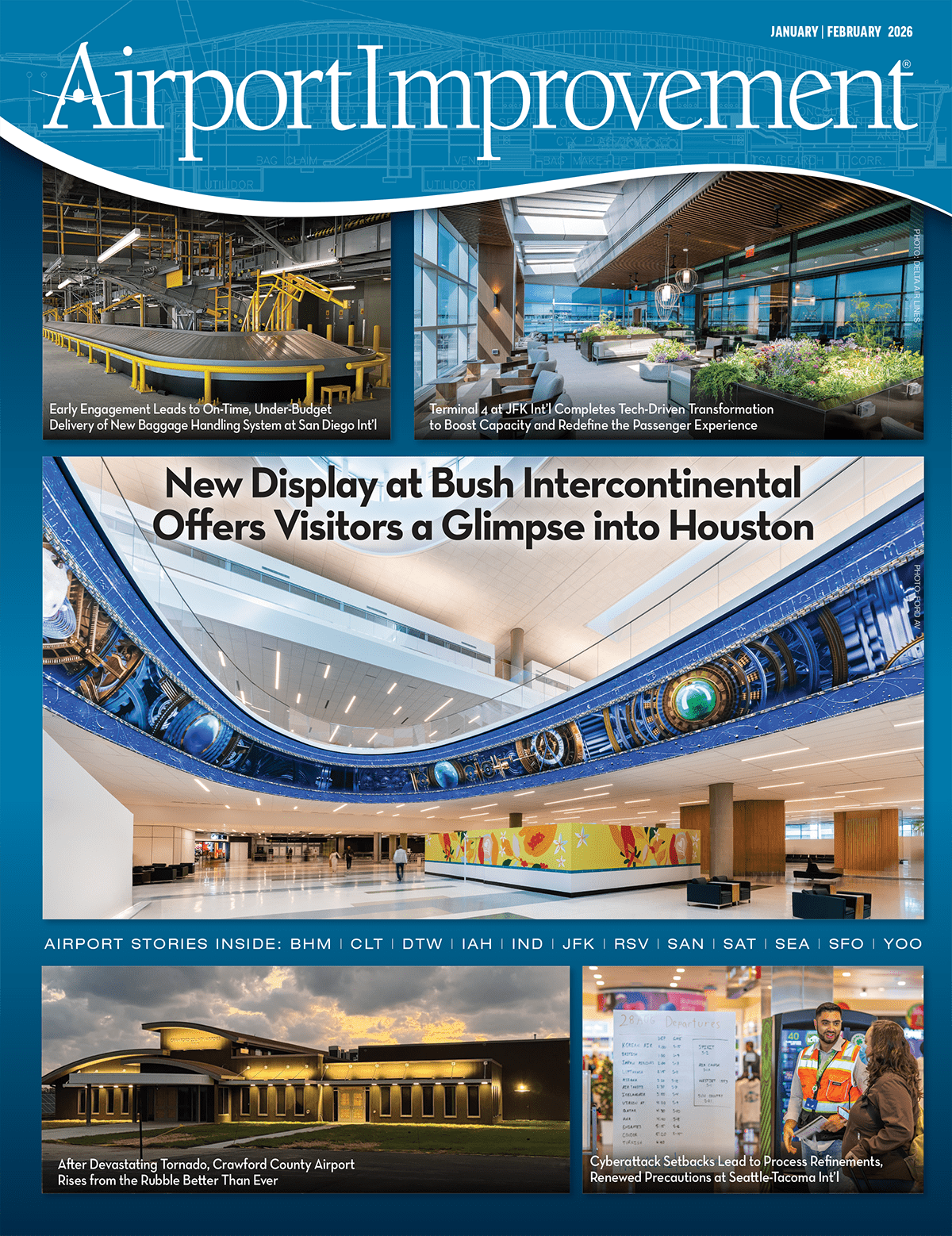

When Hampton Roads Airport (PVG) in Chesapeake, VA, went on the market through a bankruptcy auction, most people saw a tract of marshy land with old runways and a few rickety buildings. But Steven Fox and two other principals of Virginia Aviation Associates LLC saw the chance to preserve a historic airfield and develop it into something even better.

In May 2000, the trio purchased the 60-year-old general aviation airport for $2.3 million. Since then, a flurry of improvements worth about $80 million has occurred, including construction of a new terminal, a runway with full parallel taxiway, and several hangars.

In May 2000, the trio purchased the 60-year-old general aviation airport for $2.3 million. Since then, a flurry of improvements worth about $80 million has occurred, including construction of a new terminal, a runway with full parallel taxiway, and several hangars.

Although his career was in real estate, Fox is no stranger to aviation or entrepreneurship as a third-generation pilot following his grandfather and father, who were both aviators and food company executives. Fox and his partners were not in the market to buy an airport, but serendipity came calling when they were asked to help settle PVG’s assets. A shared love of aviation and a desire to save the airport inspired the trio of associates to purchase PVG. There wasn’t much on the wet 230 acres—two runways without lighting or an instrument landing system and a few tenants, including Backus Aerial Photography, which has been at the airport since 1955 and remains there today. But the parcel was near four main highways, a major seaport and a larger international airport. In short, the three partners saw potential.

| FACTS&FIGURES

Project: Airport Development Location: Hampton Roads Executive Airport, Private Owners: Steven & Bee Fox Annual Operations: About 90,000 Based Aircraft: 165 Tenants: 25+ aviation-related businesses, including initial/commercial/helicopter flight schools, 135 charter operators, several jet & turbine management companies, two upset recovery flight training providers, STEM school foundations & other non-profits, medical emergency providers, a Robinson helicopter dealer & utility line inspection helicopter companies Development Timeline: May 2000-present Key Milestones: Terminal opened May 2011; new 5,350-ft. runway opened Sept. 2014; parallel taxiway opened Oct. 2015 Airport Development Consultant: Talbert & Bright Initial Site Development Costs: $55 million (utilities connections, runway/parallel taxiway construction, terminal & hangars) Funding: State & federal grants; private funds from owners at the time (Virginia Aviation Associates) Geogrid to Stabilize Airfield Soil: Tensar TX5 Earthwork for Runway & Taxiway: 925,000 cubic yds. Asphalt for Runway & Taxiway: 28,000 tons Asphalt for Apron & Other Pavement: 10,000 tons Pending Projects: 36,000-sq.-ft. jetport complex with advanced air mobility research & training center; additional hangars; parking aprons; charging stations for electric aircraft Cost: $10 million Funding: $6.5 million from VA Dept. of Aviation Historical Background: Airport was built in the 1940s under the GI Bill & has always been privately owned. Retired U.S. Army Capt. Henry Pascale, one of the original investors/owners, later re-purchased it at a foreclosure sale for $25,000 & owned it again until he died at age 95 in 1990. |

The vision was to create an airport for private and corporate aircraft operators, and the new owners signaled their intentions by promptly changing the airport’s name to Hampton Roads Executive. One year later, they bought 404 more acres for $4.2 million to cement their vision of establishing an airport that would eventually accommodate turbine aircraft and become a general aviation reliever for Norfolk International Airport (ORF), about 20 miles to the northeast.

Fox ultimately bought out one of the other two principals of Virginia Aviation Associates (his father, Jack Fox) and survived the early passing of his friend, helicopter instructor and third partner, David A. “Andy” Gibbs. Steven Fox became majority owner with his wife, Bee, a retired assistant city attorney for Virginia Beach who now supervises marketing for the airport and works with its law firm. Son Luke serves as director of finance and managing engineer.

A Real Fixer Upper

For 60 years, PVG only served piston-powered aircraft. Now, the goal was to create an executive airport for turbine aircraft, turbine aircraft management companies, Part 135 operators and associated peripheral companies. But the old 4,000-foot runway was not long enough for such traffic. Most of the turbine aircraft Fox aspired to attract require at least 5,000 feet. “We knew we needed that new runway,” emphasizes Fox.

The fledgling airport also needed a fuel farm, hangars, office buildings and a terminal. “We went to both state and federal agencies to tell our story about growing the airport, and they educated us very quickly on what financial help was available,” Fox recalls.

Given the airfield’s soggy soil conditions, Fox initially hired an engineering firm to perform wetlands and environmental studies, but in 2004, he contracted Talbert & Bright of Richmond, VA, for the larger airport development project. It completed PVG’s new 5,350-foot east-west runway, full-length parallel taxiway, runway and taxiway lighting and instrument landing system, and continues to serve as the airport’s consultant for current and future projects.

“Our job is to take the big picture and break it down into workable parts that ultimately deliver the end goal,” says Project Manager Steven Peterson, P.E.

He and Project Engineer Chris Jaeger, P.E., created a capital development plan to maximize federal and state grants, produce designs and coordinate contractors for various projects.

The firm provided site design for 14 T hangar buildings (each with 10 units) on the west side of the airfield, a site selection study and design work for the terminal building, additional hangar projects, and preliminary design for the runway project. The latter included a topographic survey, soil borings, coordinating with FAA, and conceptual phasing for the runway development.

Funding support is ongoing for current and future Airports Capital Improvement Plan (ACIP) projects with the FAA Airport Improvement Program providing 90% and the Virginia Department of Aviation providing 8% percent, leaving 2% for the airport’s share.

Fox explains that until this year, all funding for the runway, taxiways and associated lighting was from ACIP, and most other sitework projects were state-funded, usually at 80/20, with a few exceptions for the terminal. Buildings other than the terminal did not qualify for federal or state funds.

The total investment through Phase III (current Main Entrance and South Apron projects) will be approximately $80 million. About $30 million was for the runway, taxiway, airfield lighting and related engineering/mitigation/drainage. The other $50 million paid for:

- 12 buildings that contain 89 hangars (70 T hangars and 19 large turbine hangars) with approximately 172,000 square feet of combined space

- Five large business aviation hangar buildings on the west apron—12,000 square feet each, with 90- by 28-foot doors; seven buildings with 21 piston/small turbine hangars and approximately 38,000 total square feet

- New 20,000-square-foot terminal and adjacent hangars

- Warehouse building with eight 5,000-square-foot units

- Main Entrance/Advanced Air Mobility Hangar/South Apron Complex—36,000 square feet (currently under construction)

- Wash rack and related underground oil/water separators

- Sitework for second/new fuel farm

- Public sewer connection to the city of Chesapeake’s sewer system

- Instrument landing system

- Perimeter fencing/security cameras/automatic security gates

- Self-serve fuel complex, airport beacon and weather station

- Assorted apron improvements

- Facility maintenance equipment and vehicles

Two Cities, One Runway

Most of PVG’s property is in Chesapeake, VA, but 80 acres—including 100 feet of the new runway—is in Suffolk, VA.

Knowing the project team would need permits from Suffolk to build the runway, Fox rallied grassroots support. “About 50 of our users got on a bus to go to a city council meeting to vouch for this runway,” he relates.

Having to submit separate proposals to each city board to secure approvals for site planning and zoning complicated matters for Talbert & Bright. Peterson notes that the dual track took extra time and effort but ultimately succeeded.

We’re Swamped

Portsmouth Airport, the precursor to Hampton Roads Airport, was built on marshy land in the 1940s and had three grass strips for Aeroncas, Piper Cubs and other small aircraft of the day. Given the wet airfield conditions, building a longer paved runway for larger aircraft was an entirely different matter.

The Talbert & Bright team encountered significant substrate challenges when repurposing the old 4,000-foot runway into a parallel taxiway for the new runway. “We had ‘weight of hammer’ material,” recalls Peterson, meaning there was no resistance from soil compaction when geotechnical engineers dropped a 140-pound hammer into a drilled hole. Typically, engineers measure how deep the hammer penetrates to determine soil stability. At PVG, it immediately sunk.

The Talbert & Bright team encountered significant substrate challenges when repurposing the old 4,000-foot runway into a parallel taxiway for the new runway. “We had ‘weight of hammer’ material,” recalls Peterson, meaning there was no resistance from soil compaction when geotechnical engineers dropped a 140-pound hammer into a drilled hole. Typically, engineers measure how deep the hammer penetrates to determine soil stability. At PVG, it immediately sunk.

“The subgrade soils in the old runway were not sufficient, so a reconstruction was needed,” says Peterson.

Areas under the new runway required about 24 inches of undercut, but the parallel taxiway required 3 to 4 feet of undercut to achieve a base that would allow application of a geogrid to further stabilize the base soil. In total, crews installed about 110,000 square yards of Tensar TX5, a tri-axial geogrid, under the new runway and taxiway. Earthwork totals amounted to 320,000 cubic yards of onsite excavation plus 605,000 cubic yards of imported sand fill to build up the runway and taxiway complex.

Hold the Line

As if soil challenges weren’t enough, there was a key city water line under the site for the new runway. In addition, its extra length created a conflict with a high voltage line that serves the city of Chesapeake’s well sites located at the north side of Runway 10-28.

“We had to coordinate with Dominion Power to expose the line and install the new drainage structures underneath the power lines,” says Peterson. To facilitate future maintenance, designers added a pair of 6-inch PVC conduits encased in concrete. One is a split duct that wraps around the existing cables.

The new runway also had to cross a 20-inch water line on the northwest side of the airport. “It was the main raw water line for two of the city of Chesapeake’s well sites,” notes Jaeger. The Talbert & Bright team designed a vertical offset to the existing water line to provide at least 12 inches of vertical separation between it and the drainage piping. Designers also specified a 30-inch steel split casing on the water line in the proposed runway pavement area that extends 20 feet on each side of the runway for a total of 140 feet.

The new runway also had to cross a 20-inch water line on the northwest side of the airport. “It was the main raw water line for two of the city of Chesapeake’s well sites,” notes Jaeger. The Talbert & Bright team designed a vertical offset to the existing water line to provide at least 12 inches of vertical separation between it and the drainage piping. Designers also specified a 30-inch steel split casing on the water line in the proposed runway pavement area that extends 20 feet on each side of the runway for a total of 140 feet.

Ahead of Its Time

With utilities and soil challenges overcome, the runway, taxiway and apron were ready to be paved. Because the airport is located directly on U.S. Highway 58, crews had to coordinate a constant stream of truck deliveries, each loaded with 20 tons of asphalt, moving along the busy roadway. In all, contractors trucked in 28,000 tons of asphalt for the runway and taxiway, plus 10,000 tons for aircraft parking and other paved areas.

The new 5,350-foot runway opened in September 2014 and the new parallel taxiway opened in October 2015. Project leaders from Talbert & Bright consider building the runway while keeping the airport operational a major success. “Everything at the airport was impacted during all of the construction, but nothing was shut down,” Jaeger reports.

Peterson highlights the project pace. “From start to finish, everything involved with the planning, designing, construction of a runway takes about 20 years to get to completion,” he explains. “So finishing it within 15 years is a big accomplishment with everything else that needed to be done.”

New hangars and a 5,350-foot runway with instrument landing system are helping attract tenants.

Private vs. Public

According to the FAA, there are approximately 14,400 private-use and 5,000 public-use airports, heliports and seaplane bases in the United States. Approximately 3,300 of the public-use facilities are included in the National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems (NPIAS) and potentially eligible for Airport Improvement Program funding. As a privately owned, but public-use airport, PVG experiences both the advantages and challenges of belonging to the NPIAS network.

The biggest perk is funding. “The government has been the best part of owning the airport, as most of the staff are aviation enthusiasts,” Fox says, adding that Virginia has one of the most robust, cutting-edge aviation agencies in the country.

Another potential advantage of private ownership is nimble management. Fox notes that decisions and funding at PVG can happen within hours, while similar matters at municipally owned airports often take weeks or months. This allows him to respond more quickly to tenant needs and requests.

Fox also considers the ability to draft his own team a big plus. “Our professional management, concierge/fueler staff and maintenance team have made the difference in the growth of the airport,” says Fox. The Hampton Roads region has a skilled and passionate workforce that includes retired aviation professionals with valuable experience, he adds.

The challenges, however, come at a price. For instance, privately owned airports have expenses for property taxes and utility infrastructure that most municipal airports do not.

Owners invested $2 million to build a new terminal that would appeal to a more executive clientele.

“We pay about $300,000 per year in real estate taxes,” Fox shares. “We are responsible for 100% of the buildings and utilities. We coordinated hook-up to the public sewer and electrical, fire hydrants and internet. The state and feds consider those ineligible items.” However, the state has recently made broadband and three phase electric power eligible items.

Moreover, because PVG is a public-use airport, Fox says he must operate 24/7. “And we pay to be open,” he adds. Virginia Aviation Associates runs the FBO, which operates from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. daily and is a Titan Aviation Fuels distributor and marketer.

Economic Incubator

Just 16 months after the partners purchased PVG, the 9/11 attacks and associated aftermath shook up their vision for the airport. “We went into ‘What can we do for our people?’ mode and began helping those who were stranded get back, and helping those who lost loved ones,“ Fox recalls.

Moving forward, the mantra of “What can we do for our people?” shaped the airport’s business model as an economic incubator and continues to influence Fox’s operating philosophy. For instance, PVG does not run a charter operation. “I do not compete with a single tenant here,” he explains.

His pitch to tenants and customers is that PVG is operated by people who understand aviation and the needs of both business and recreational aircraft owners—and this reinforces their investment in the airport.

Along with the new mile of runway, there are many different sizes and shapes of hangars.

“We have not built just one type,” says Fox, noting that PVG has more than 500,000 total square feet of hangar space. “If a business outgrows its current space or wants to downsize, there is likely a space to move into.”

Throughout the years, the airport has expanded from having a handful of tenants to more than 25 aviation-related businesses, including flight schools, charter operators, aircraft management companies, etc.

One of the current tenants, Hampton Roads Charter Service, has been based at PVG since 2005. Dave Hynes, its president and co-founder, started the company with the late Andy Gibbs, who later became a partner in Virginia Aviation Associates. After watching PVG evolve and grow for nearly two decades, Hynes says that operating at a privately owned airport has been terrific. “Hoops to jump through at a public- or government-owned airport can be cumbersome,” he adds.

A steady supporter, Hynes has plenty of praise for PVG. “Hard to call out any one thing,” he remarks. “The expansion and the quality of the new runway have allowed us to operate the jet fleet that we do. Ramp projects and bigger hangars have been beneficial. We have a good, mixed-use community.”

Reflections of a Private Owner

While buying and operating a public-use airport certainly isn’t for everyone, Fox emphasizes the importance of hiring a team of professional, hardworking people in all areas—legal, finance, environmental, engineering, etc. Effective management has been critical to navigate the funding process, compliance issues, construction challenges and personnel requirements.

“The plan worked,” he says. “It wasn’t me; it was having a great team.”

With previous investments reaping returns, PVG is acting as the economic incubator Fox and his associates envisioned almost a quarter-century ago. For the next act, millions more dollars are slated for a jetport complex with infrastructure to support advanced air mobility aircraft and alternative fuels to keep improving and moving this classic airport forward.