The first on-site hotel at John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) is a nostalgic 1960s flashback thanks to the recent transformation of architect Eero Saarinen’s iconic TWA Flight Center into the new TWA Hotel. Scheduled to open in mid-May, the facility is a tribute to the golden age of jet travel, complete with swanky red carpeting, elegant white staircases and a sunken cocktail lounge that serves martinis, Old Fashioneds and other vintage favorites.

The first on-site hotel at John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) is a nostalgic 1960s flashback thanks to the recent transformation of architect Eero Saarinen’s iconic TWA Flight Center into the new TWA Hotel.

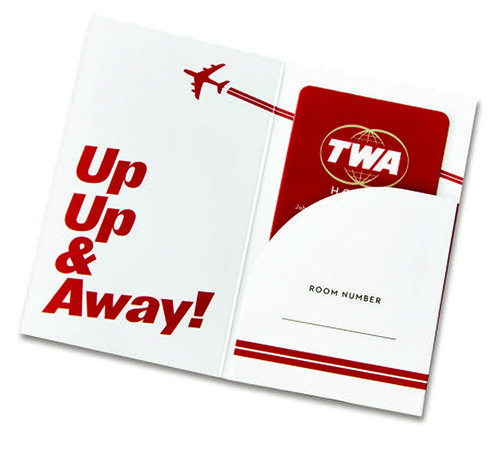

Scheduled to open in mid-May, the facility is a tribute to the golden age of jet travel, complete with swanky red carpeting, elegant white staircases and a sunken cocktail lounge that serves martinis, Old Fashioneds and other vintage favorites. In short, it looks like somewhere Mad Men’s Don Draper and Roger Sterling would take clients for a long night of drinking and Sinatra music. And there’s TWA branding at every turn.

The $230 million renovation and construction project was executed by a public-private partnership between MCR/Morse Development, JetBlue and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

|

Project: Renovating 1962 TWA Flight Center into New TWA Hotel Location: John F. Kennedy Int’l Airport Cost: $230 million Size: 512 guest rooms; 200,000-sq.-ft. hotel lobby; 50,000-sq.-ft. conference center; 10,000-sq.-ft. observation/pool deck Project Format: Public-Private Partnership Lead Developer & Investor: MCR/Morse Key Partners: MCR; JetBlue; Port Authority of New York & New Jersey Hotel & Conference Center Design: Stonehill Taylor Architects, P.C. Construction: Turner Construction Co. Glass Curtain Wall on Hotel: Fabbrica Hotel Millwork: Highland Wood Products; Hilltop Woodworking Sunken Lounge Operator: Gerber Group Cogeneration Plant Enclosures: Epsilon Industries Of Note: First on-site hotel at JFK; 1960s décor & furnishings; retro cocktail lounge; noise-minimizing glass curtain wall; vintage jetliner displayed on the tarmac |

“JFK is embarking on a sweeping redevelopment as part of Governor Cuomo’s vision of a new JFK that will make it a model of modern airport facilities internationally,” explains Don Free, the airport’s program director for aviation business development. “With every JFK terminal looking at undergoing a rebuild or major addition as part of the $13 billion redevelopment, the TWA Hotel and Conference Center project is a welcome addition to the JFK landscape, an iconic new structure that will help set the bar for the entire airport.”

Executives from MCR/Morse, the project’s developer and lead investor, emphasize the significance of the new hotel. “Having a place for passengers and customers to sleep that is walkable from all the terminals is a big deal,” notes Chief Executive Officer Tyler Morse. “That amenity has never existed before at JFK. Heathrow has five on-airport hotels, DFW has three…but JFK never had one until now.”

The project was a labor of love for Morse, because it combined two of his longtime passions: aviation and hotels. “I’ve admired this building forever and the ability to bring it back to life was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” he reflects.

Amid the facility’s many vintage details, such as replicas of swizzle sticks from TWA’s signature in-flight drinks, are two intentional anachronisms: the absence of cigarette smoke and the addition of high-speed Wi-Fi.

Building on History

In its heyday, the TWA Flight Center was a glamorous and bustling airline terminal. But after the once-dominant carrier went out of business, the building sat unoccupied since 2001. Eventually, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey hired MCR/Morse to turn the mothballed facility into a hotel.

“The TWA idea was our concept to bring back the incredible history and legacy of the carrier,” Morse explains. “We bid competitively and beat out related groups, including Donald Trump’s company.”

Crews began work in fall 2016 and completed the project earlier this year. Turner Construction Company led efforts to renovate the historic flight center and construct new hotel/conference center facilities.

Extensive work was required to restore the structure that opened back in 1962 to its former glory. “When we got in there, the building still had asbestos, lead paint and non-tempered glass,” recalls Morse. “All of that had to be replaced and abated.”

Designers repurposed the flight center, famous for its futuristic winged architecture, into a 200,000-square-foot lobby for the new hotel. “It’s the largest hotel lobby in the world and is the entirety of Saarinen’s building,” Morse says.

The expansive space includes high-end retail outlets, six restaurants and eight bars. The Sunken Lounge contains a conversation pit and chili pepper red carpeting—both signature Saarinen creations. Gerber Group, a New York City firm that specializes in innovative bars and restaurants, operates the retro cocktail lounge.

A 50,000-square-foot event and conference center, capable of accommodating 1,600 people, is situated behind the lobby. Guest rooms are located in two seven-story buildings that were constructed behind the former flight center. There is also a 12,000-square-foot ballroom/pre-function space and a 10,000-square-foot observation and pool deck.

The new development connects to JFK’s Terminal 5 (where JetBlue operates) via Saarinen’s flight tubes, which film buffs may remember from the movie Catch Me If You Can. “You can walk from our building right into Terminal 5,” Morse says. The AirTrain, which loads/unloads in front of the new facility, transports passengers to the airport’s nine other terminals.

Careful logistics were required during construction of the two hotel buildings and conference center because the worksite was essentially landlocked by Terminal 5, the Flight Center building and the two flight tubes. “Navigating the construction area was a challenge,” recalls Turner Project Executive Gary McAssey. “We had to dig under the existing tubes to create a passageway to get heavy equipment back and forth from the conference center.”

Because the development was hemmed in, construction crews had to dig deep. The conference center, for example, is 30 feet below grade and 25 feet below the water table of nearby Jamaica Bay. “Since water travels easily through sand, the biggest challenge was keeping the grade dry so we could complete construction,” McAssey explains. “We had a high-powered dewatering system pumping 2,000 gallons a minute 24 hours a day, seven days a week for eight months.”

Project designers also had to ensure the stability of soil around the construction area, which was closely monitored in real-time. Instead of driving sheet piling and spending millions of dollars on steel, crews used two innovative SOE (support of excavation) systems to stabilize the ground. Workers created special material mixes by using an excavator and 42-inch auger to blend 7.7 million pounds of cement into deep soil.

Special Requirements

Morse says the most challenging aspect was navigating the numerous government agencies involved with the project, predominantly the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the city of New York, 14 preservationist groups and eight federal agencies, including the FAA because the work involved a change to the airport’s layout. “We also completed an environmental review of the project, which was very complex and time-consuming,” he adds.

The design process received considerable emphasis. “We could have put hotel rooms in the flight center, but we opted to construct them separately because we didn’t want to overwhelm the existing building,” explains Morse. “We were careful to highlight Eero Saarinen’s masterpiece while adding hotel rooms, restaurants and other accouterments.”

The design process received considerable emphasis. “We could have put hotel rooms in the flight center, but we opted to construct them separately because we didn’t want to overwhelm the existing building,” explains Morse. “We were careful to highlight Eero Saarinen’s masterpiece while adding hotel rooms, restaurants and other accouterments.”

Guest rooms feature floor-to-ceiling, full-width windows to highlight views of the flight center building and the airport’s busy runways. A 4½-inch thick, triple-glazed curtain wall with special transmission glass was engineered by Fabbrica to cancel associated aircraft noise. According to company officials, the JFK hotel has the second-thickest glass wall in the world, behind only the U.S. Embassy in London. TWA Hotel curtain wall includes 2,000 glass panels, each weighing 1,600 pounds.

“When you stand in the rooms, it is dead silence,” McAssey says. “It’s very impressive.”

All rooms are outfitted with classic midcentury modern furniture by Knoll, including Saarinen’s famous executive chair, womb chair and pedestal tulip side table. Each is also equipped with a full wet bar, rewired vintage rotary phone and TWA-branded toiletries.

The rooms’ wooden martini bars and tambour walls were custom-built by 200 Amish woodworkers from Ohio using locally grown walnut trees. The massive project required 20 semitrailers of logs and took five months to complete. In true Amish fashion, nothing was wasted. Unused lumber pieces were tossed into factory furnaces for heat, and sawdust was turned into bedding for horses and cows.

Renovation of the former Flight Center involved some structural alterations to the historic building as well as restoration or replication of the original tile and lighting. McAssey reports that the tiling work was particularly tedious because many of the floor penny tiles were damaged. “It was painstaking work,” he says. “The hard part was tying the new section into the old section. The crew literally had to grind each tile.”

Renovation of the former Flight Center involved some structural alterations to the historic building as well as restoration or replication of the original tile and lighting. McAssey reports that the tiling work was particularly tedious because many of the floor penny tiles were damaged. “It was painstaking work,” he says. “The hard part was tying the new section into the old section. The crew literally had to grind each tile.”

Workers also recreated the structure’s historic structural pillars, recoated the winged roof and restored damaged sections to match original geometry.

Beyond the unique requirements of historic renovations, Turner Construction encountered challenges typical of other North American airport projects: having a competent labor workforce available and keeping a close eye on the bottom line.

“There is tremendous pressure on pricing for materials and equipment that are incorporated in these major aviation projects,” notes Jay Fraser, the company’s vice president and general manager of Aviation. “Strong local presence and familiarity with local markets as well as regional and national labor suppliers and specialty contractor providers is key to manage the challenges associated with labor and material resources.”

“There is tremendous pressure on pricing for materials and equipment that are incorporated in these major aviation projects,” notes Jay Fraser, the company’s vice president and general manager of Aviation. “Strong local presence and familiarity with local markets as well as regional and national labor suppliers and specialty contractor providers is key to manage the challenges associated with labor and material resources.”

In order to minimize interruptions, Turner scheduled some crews to work between 11 p.m. and 4 a.m., when JetBlue was not operating at the terminal. “The majority of our aviation projects involve complex expansion, renovation and modernization projects that occur on active airport properties,” Fraser says. “Planning, organizing and executing construction operations so they occur safely and do not impact passengers or ongoing airport operations is of critical importance.”

Environmental Features

MCR opted to install its own CoGen (cogeneration) power plant, which earned LEED Silver status. “We did it for a combination of economic reasons and environmental reasons,” Morse explains. “We can generate power for a lot less than buying it from the grid. And, the Port Authority was supportive of doing a microgrid-type of format. It’s a better mousetrap.”

While some people may consider the move a risk, Morse notes that the local grid is not that stable. “We did the right thing for the environment and the right thing for the project,” he comments.

The 4,000-square-foot CoGen building was prefabricated off-site to save time and space. That also allowed the contractor to start work on the plant six months before the facility was prepared to accept it. “Traditionally, you would construct a CoGen plant on the job,” explains McAssey. “But if we would have built the plant in place, construction would have started in March 2018. Instead, we were able to start the fabrication and assembly of equipment in the prefab enclosures in September 2017.”

The CoGen plant, which has a natural gas feed, was fabricated in 10 sections, each completely fitted out with equipment and fully piped. The sections were installed atop the north hotel building on a 6-inch floating slab to mitigate the operating noise. “When you’re in a room, you can’t hear any aircraft or even the CoGen plant which sits above it,” McAssey says.

In a separate voluntary initiative, ground material from the project helped reinforce the nearby Spring Creek Park, a wildlife refuge in the Gateway National Recreation Area along the Jamaica Bay shoreline. MCR/Morse Development donated roughly 74,000 cubic feet of sand excavated from the TWA Hotel site to the National Park Service. The sand, valued at about $5 million, will help reduce the risk of storm damage and flooding in a neighborhood that was devastated by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. The donation supports efforts to restore more than 225 acres of wetland and coastal forest.

Celebrating the Sixties

The new hotel and conference center hinges on 1962, when the TWA Flight Center originally opened. “It was a very special year—not just in aviation, but also in America,” explains Morse. “Dr. No, the first James Bond movie, came out; it was Camelot, and Kennedy was president. Spiderman came out that year, and so did the Jetsons, the first color TV show on prime time.

“John Glenn had just circled the Earth, and the Cuban missile crisis was going on,” he continues. “It was the epic struggle of Capitalism versus Communism, and the total reformation of the Catholic Church, with Mass going from Latin to English. The Barbie Dream House came out that year, the supersonic jet was in development, the microwave oven premiered…1962 really was an amazing year and celebrating it is a big deal.”

Airport officials also highlight the project’s link with the past. “The airport has a rich history with TWA, and the opportunity to bring back the TWA brand was a major selling point,” says Free. “It is a first-rate hotel for a first-rate airport. As a result, the TWA Hotel will play a major role in the overall creation of a world-class JFK.”

Quick Ascent

Public interest in the project has been strong. In fact, when the hotel opened for reservations on Feb. 14, its website crashed. “Thousands of people were booking rooms from all over the world—from Perth to Singapore, and the U.K. to Russia,” Morse explains. “People are very excited about it.”

He also anticipates strong interest in the conference center’s meeting rooms and ballrooms for corporate and private events. “We think we will average 100 weddings and 50 bar/bat mitzvahs a year,” he predicts. “A Delta pilot and Southwest flight attendant actually postponed their wedding for a year so they could get married in our building.”

If the current array of restaurants and bars isn’t enough, a 1958 TWA Lockheed Constellation jetliner is being transformed into another cocktail lounge. Once completed, the restored aircraft will be parked on the tarmac, with full views from the Sunken Lounge.

MCR also developed the TWA Lounge at 1WTC, a satellite event space lounge on the 86th Floor of the One World Trade Center building. The lounge is decorated with TWA memorabilia, David Klein poster art, a sunken lounge with chili pepper red carpeting, vintage TWA uniforms and a custom Solari departure board.

The lounge offers a clear view of JFK, and a telescope in the lounge points directly at the new TWA Hotel. “We wanted to make a psychological connection between the city of New York and the project at the airport,” Morse says. “It’s been our staging area for a TWA museum we want to eventually build at JFK.”

facts&figures

facts&figures