|

|

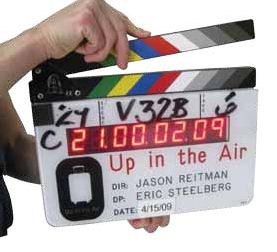

Although the film portrays nearly a dozen airports, it was shot at five. Lambert-St. Louis International, for instance, was transformed to look like O’Hare and Dallas-Fort Worth International. It also stands in for unnamed airports in Omaha and Miami, even though crews also shot at Miami International and Omaha’s Eppley Airfield.

“When a script includes an airport scene, we’re never quite sure how we’re going to pull it off,” notes executive producer Michael Beugg. “Access is tough, and it’s a challenge to reconcile the airport’s security issues with the peculiarities of the filmmaking process and creative wishes of the director and actors.”

Many productions shoot at vacant terminals to save time and minimize complications. Ontario Airport, just east of Los Angeles, is a popular close-to-home choice for many studios. Director Jason Reitman, however, preferred the authenticity of shooting in active terminals for Up in the Air.

“The way the characters interact with the airline and airports is integral to the storyline,” explains Beugg.

|

The philosophical shift apparently began at the top. “Some directors expect to do as they please, whatever the location,” explains Beugg. “Jason recognized that regular operations at the airports – and all the safety and public access aspects they involve – had to be a top priority. That made a huge difference getting the shots he wanted.”

St. Louis Spirit

Most of the film’s airport scenes were shot at Lambert. According to Reitman, the airport wasn’t just a shooting location; it transcended into an uncredited character. “The beauty and history of its design left an indelible mark on the film,” he notes.

The airport, in fact, helped convince Paramount Pictures to base the film in St. Louis. A 35% tax credit from the state of Missouri was important; but the airport’s cooperation really sealed the deal, says Missouri Film Commission director Jerry Jones.

“The airport was very film-friendly,” notes Jones. “Everyone worked extremely hard to allow the production company to do what they needed to do while maintaining the usual strict security measures.”

|

“Clearly, financial profit wasn’t our motive,” explains Lea. “It was a break-even project. We supported the film for what it would bring to the overall region.”

By conservative measures, it brought in at least $12 million. According to Jones, the film’s “direct spend” (equipment, local labor, ground expenses, etc.) was $11.8 million, but its overall economic impact was far greater. “There’s definitely a multiplier effect and plenty of indirect spending,” he qualifies.

The airport did, however, bank a major marketing bonus when Reitman changed the script to have George Clooney’s character gush about the architectural glory and historical significance of Lambert.

“You couldn’t ask for a better promotion for the airport,” enthuses Lea.

“It was like a celebrity endorsement we’d never be able to afford,” adds Jones.

The airport, however, also experienced the less glamorous side of the film business. After sixth months of preparation, a rainstorm the first day of production obliterated the detailed shooting schedule Lea and studio personnel had mapped out.

Previous experience filming The Informant in 2007 and The Lucky Ones in 2008 helped airport staffers roll with the changes. Beugg also suspects Lea’s former career as a television news reporter enhanced his understanding of what it takes to get the “perfect shot.”

Paramount personnel, in turn, impressed Lea with their flexibility and perseverance to get the job done. Crewmembers automatically sprang to the rescue when a real passenger’s car got stuck in the fake snow created for scenes shot outside the arrivals area.

Motor City Glam

Detroit Metropolitan Airport was another primary airport location for the film – especially airside footage. “We had a beautiful, snowy Detroit day, so they shot a lot of takeoffs and landings,” recalls Scott Wintner, head of public relations for Wayne County Airport Authority and pointman for the film project.

“Due to the nature of airport activities, you can’t just turn them loose and let them do their work,” Wintner explains. “We became an integral part of their production crew, and they, in essence, became part of the airport staff.”

Wintner was especially pleased, but not surprised, when a shot of the airport’s McNamara Terminal was chosen for the movie posters, billboards and DVD cover. “It’s very photogenic,” he notes.

“It had the modern, high-end look we needed,” explains Beugg. “The red train zipping through really caught the director’s eye.”

In contrast, the airport’s older, out-of-commission Berry Terminal provided a wood-paneled look that passed for smaller airports with regional airline service. The North Terminal, which opened in 2008, provided yet another look for set designers.

“Being able to represent a number of different airports at one location helped hold production costs down,” notes Beugg.

Although Up in the Air cost an estimated $25 million to produce, it grossed more than $115 million by early February and snagged six Oscar nominations.

One for the Team

Like Lambert, Detroit Metro wasn’t driven to participate in the film by direct revenue opportunities. Winter estimates the airport authority netted about $96,000 for its efforts. “Our mission is to be an economic engine for the region,” he explains. “The $1.2 million the film brought into the area was absolutely worth the extra effort at the airport.”

Experience guided the airport’s expectations and preparations. Since July 2008, the airport has hosted nearly 30 different television, film and print media projects. Last year, six feature films shot there. While most involved two to three days with scouts and a few days of prep work, Up in the Air consumed almost all of Wintner’s time for three months – a line item that wasn’t included in the $10,000 of labor expenses charged to the studio.

“It’s easy to underestimate the true cost of having a major film with named talent shoot at your airport,” he advises. “It’s much more than hiring extra security. We didn’t charge for a lot – like floor diagrams for the production crew or overhead costs such as power or extra cleaning to have the facility camera-ready.”

Airport crews also changed lighting and removed a bench from the intra-terminal passenger train to facilitate shooting.

“At the same time,” Wintner adds, “it’s hard to fully value the positive boost a film like Up in the Air has on employee morale. People really enjoy telling their friends and family they were part of filming a big-name movie.”

Wintner brought a unique perspective to the project having previously worked for film and airport trade associations (the Motion Picture Association of America and Airports Council International – North America). As such, he brought a clear understanding of the filmmaking process to the table when briefing the producers about airport procedures and logistics. The nature of the script (no special effects, airplane crashes or disgruntled traveler scenes) simplified his task.

He also issued memos to airport employees stressing the importance of maintaining a normal workflow and resisting the urge to act like paparazzi. “They were extremely respectful of the work the cast and crew had to get done,” he reports.

Airline employees, however, showed less restraint – leaving their workstations or showing up late for shifts because of the distractions.

According to Wintner, airside shoots were logistically simpler than landside scenes. “On the airfield, it was just the director and cameraman in an airport operations vehicle,” he explains. “Inside an active terminal, we had hundreds of people in the cast and crew to manage, plus the public.”

Fandemonium

Crowd control was by far the biggest challenge at Detroit Metro. “We sorely underestimated the lengths women will go to just to get close to George Clooney,” Wintner laughs. “We had one passenger kick off her heels and run all the way to the other side of the terminal in nylons – that’s about a mile. She was completely willing to miss her flight just to get a glimpse. There was constant hysteria around Clooney.”

Members of the media used a variety of tactics to gain access to post-security areas. Some, report airport personnel, were rather underhanded.

Crowd control was less of a challenge at Lambert. “Crews had been filming throughout the city for weeks, so ‘Clooneywatch’ wasn’t as frantic when it was time to shoot at the airport,” explains Lea.

Airport executives were consequently able to enjoy watching passengers’ reactions as they spotted the mega-star. “Between airport staff and the production assistants, we were able to give them a quick glimpse and keep them moving,” relates Lea. “They were more cooperative about not taking pictures and staying behind the barricades than we anticipated.”

A scene that shows George Clooney’s character passing from the airport’s Brooks Brothers store through the middle of Concourse C was the most difficult to manage. Foot traffic was stopped for one to two minutes at a time for shooting, then film crews waited for another clear opportunity.

“When passengers could see what was going on, they were very understanding,” Lea recalls. “Most got a real kick out of it.”

Beugg was similarly relieved when travelers enjoyed a behind-the-scene look instead of growing indignant about being slowed down.

Clooney’s humility unintentionally made security more of a challenge at Detroit Metro. “He didn’t want the fuss of a large entourage,” explains Wintner, “so we had to adjust security coverage as people realized he was there.”

At all the airports, the box-office dynamo received universal kudos for taking ample time to sign autographs and pose for fan photos – often under the watch of undercover security agents.

What it Takes

Paramount considered a wide variety of factors when choosing airports for Up in the Air. Lambert’s non-stop airline service to Los Angeles was a major boon for production staff commuting home on the weekends. The airport also offered attractive catering arrangements, access for equipment vehicles and ample waiting areas for extras.

Willingness to work with film crews, however, was pivotal. According to Beugg, McCarran International in Las Vegas was the least star-struck of the five airports involved with the film. “They were very upfront with concerns about the film inconveniencing passengers on their way to the hotels and casinos,” he recalls. “Omaha, on the other hand, doesn’t get many filming requests and was pretty excited.”

|

Filming behind an airport security checkpoint can be a pain in the … shooting schedule. Filming at a checkpoint was simply unheard of – until recently. Paramount Pictures cleared all the necessary hurdles with the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to film Up in the Air at two checkpoints in Lambert-St. Louis International last April. “There were a lot of legal steps and agreements necessary to make it happen, including a full review of the script,” notes Bobbie Faye Ferguson, director of the Office of Multimedia for DHS. “We can allow ‘feasible fiction,’ but we needed to make sure scenes were as accurate as possible.” Adding footage of a transportation security officer (TSO) inspecting boarding passes, for instance, was one of the minor changes DHS required. “The studio was very intent on being accurate,” recalls Ferguson. “They literally sat us right next to the executive producer, who kept asking if everything was correct and making sure they didn’t film anything they weren’t supposed to. They wanted to get it right and were great about following all of our policies, rules and procedures.” Crews worked overnight to ensure that no passengers were inconvenienced – a major contractual condition of both TSA and Lambert. The first night, shooting wrapped between 2 and 3 a.m.; the second night, crews finished after 5 a.m., just minutes before the checkpoint needed to reopen for real passengers. Because actors couldn’t be trained to use TSA screening equipment, actual TSOs appear in the film. According to federal guidelines, however, they couldn’t be paid for such ancillary duties; so 25 Lambert TSOs volunteered their time for the project. DHS ethics and legal officials provided necessary clearance for the off-duty use of TSA uniforms.

Granting film crews such unprecedented access to a checkpoint provided TSA with a high-profile, mass-market opportunity to educate the public about standard security procedures. “It was also a great way to highlight the good work our officers do day in, day out at airports around the country,” notes Carrie Harmon, the TSA regional public affairs manager that helped supervise filming. “Our highest priority, though, was ensuring that security was never compromised and passengers were not inconvenienced – even the few late night fliers who passed through when we shot at an open checkpoint.” Dennis Thompson, assistant federal security director for screening at Lambert, spent two to three months working out logistics for the shoots. Airport public relations manager, Jeff Lea, logged 20-hour days when crews filmed at checkpoints. Lambert and Detroit Metropolitan, another main location for general airport footage, took decidedly different approaches to clearing film personnel and equipment through security. Lambert set up a temporary screening area just for the film, then bused cast and crewmembers to various shooting locations with special escorts. In Detroit, film personnel passed through the same security checkpoints as passengers. “Each system had its virtues,” recalls executive producer Michael Beugg. “Not having to wait in line with passengers saved time in St. Louis, but having a hotel right in the airport saved time in Detroit.” Both airports issued a limited number of temporary security badges to select members of the crew such as the director and senior producers. Badgeholders still had to pass through security checkpoints, but the process was expedited since they had already undergone fingerprinting, background checks and other standard clearances. |

TSA Goes Hollywood

TSA Goes Hollywood