In the course of meeting FAA design standards for runway safety areas, Merritt Island Airport (COI) upgraded its previous grass safety zone and completed four associated environmental mitigation projects in 2016. Apparently, management’s above-and-beyond philosophy also extends to construction administration, as crews finished the $4.8 million initiative $700,000 under budget and one month ahead of schedule.

In the course of meeting FAA design standards for runway safety areas, Merritt Island Airport (COI) upgraded its previous grass safety zone and completed four associated environmental mitigation projects in 2016. Apparently, management’s above-and-beyond philosophy also extends to construction administration, as crews finished the $4.8 million initiative $700,000 under budget and one month ahead of schedule.

In the course of meeting FAA design standards for runway safety areas, Merritt Island Airport (COI) upgraded its previous grass safety zone and completed four associated environmental mitigation projects in 2016. Apparently, management’s above-and-beyond philosophy also extends to construction administration, as crews finished the $4.8 million initiative $700,000 under budget and one month ahead of schedule.

The general aviation airport’s location and airfield configuration did not make it easy. Situated on Florida’s east coast near Cocoa Beach and Port Canaveral, COI’s sole runway juts out into a nationally protected waterway. Previously, a grassy area about 60 feet long served as the safety zone at the end of Runway 29; but erosion had eaten away at it and the margins around the north side of the runway safety area throughout the years. Between 1988 and 2014, the airport had 34 aircraft roll off the 3,601-foot runway and into the surrounding Banana River Aquatic Preserve.

That streak, plus the volume and nature of its traffic, inspired COI to build a 240-foot long runway safety area, per FAA standards for larger, busier airfields. A high concentration of the 110,000 annual operations is for flight instruction, and all traffic uses the same, single runway.

|

Project: New Runway Safety Area Location: Merritt Island (FL) Airport Owner: Titusville-Cocoa Airport Authority Associated Environmental Mitigation Projects: Removing sunken boats from adjacent aquatic preserve; protecting shoreline around airfield; creating seagrass island in the most eroded area near runway; restoring local wetlands Total Cost: $4.8 million Funding: 90% FAA; 5% state; 5% airport Engineer: Michael Baker Int’l General Contractors: Welsh Construction for runway safety area, shoreline stabilization & seagrass Island; Sterling Enterprises for salt marsh Aquatic Restoration: Sea & Shoreline; Michael Baker Int’l Accolades: 2016 Florida Airports Council J. Bryan Cooper Environmental Excellence for General Aviation Airports Award; 2017 Florida Institute of Consulting Engineers Excellence Honor Award; 2017 FAA Southern Region General Aviation Safety Award; 2017 Engineering News Record Southeastern Region Airport Project of the Year Award |

“It was the airport authority itself that pursued this additional safety project,” says Michael Powell, the authority’s chief executive officer. “We wanted to ensure that we had the safest environment possible for our valued tenants and public.”

Small Airport, Big Project

Airport officials worked for about two years to secure FAA approval and funding for the project. “It is a very large project for an airport that is so small; so it took a while to get the funding,” Powell relates.

During the review process, the FAA asked the airport to complete its on-going 20-year master plan before finalizing the request. In the end, the federal agency funded 90% of the project, and the airport and state split the remaining costs equally. While the airport authority is ultimately part of Brevard County, COI is self-sustaining, notes Powell.

Constructing the new safety area required the airport to fill in 185 feet of the nearby aquatic preserve—a change that required an environmental assessment and multiple federal and state permits. By working the process in advance, the project team obtained approval for its designs and permits by August 2015, three months ahead of schedule. Overall, more than 10 local, state and federal agencies reviewed the project.

Powell notes that the airport board set the tone early by making it clear that the project should not just meet federal and state environmental requirements, it should be a model. “We are a community asset, and we need to stay focused on what the good folks in the surrounding community want and how we can best serve and improve the environment,” he explains. “We always try to be a good neighbor.”

The Jacksonville office of Michael Baker International (COI’s engineer of record) designed the runway improvements and associated remediation projects. Mariben Andersen, the firm’s environmental manager for the projects, notes that the engineering team undertook sustainability measures not required in the permits, per the authority’s marching orders. “The extra effort was the right thing to do as stewards of the environment,” says Andersen.

State and federal laws required that any environmental damage caused by fill needed for the new runway safety area had to be mitigated within the local watershed. After collaborating about possible mitigation projects with the Brevard County Department of Natural Resources, St. Johns River Water Management District, Florida Department of Environmental Protection and U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, the COI team mapped out a list of specific initiatives:

State and federal laws required that any environmental damage caused by fill needed for the new runway safety area had to be mitigated within the local watershed. After collaborating about possible mitigation projects with the Brevard County Department of Natural Resources, St. Johns River Water Management District, Florida Department of Environmental Protection and U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, the COI team mapped out a list of specific initiatives:

• removing four sunken boats from the aquatic preserve;

• protecting the eroding shoreline around the airfield;

• creating a seagrass island in the most eroded area along the runway; and

• restoring wetlands near the airport.

Extending the Field

To create a foundation for the new runway safety area, project designers determined that contractors would have to fill about one-half acre of the estuary. About 15,000 cubic yards of fill was used to create the extension and make it level with the runway. Crews pounded steel piles into the river bottom to create a barrier so the zone could be dewatered.

Work was performed at night to avoid interfering with airport operations, notes Andersen. Contractors also built a construction access road, so heavy construction equipment would not cross the runway.

Before the site was dewatered, an aquatic restoration company harvested seagrass from the area so it could be replanted later on a newly created seagrass island. “It made no sense to bury the seagrass,” Andersen notes. After the area was dewatered, crews also removed 12 inches of mud containing seagrass roots to subsequently place on top of the new island.

Project designers stabilized the runway’s shoreline and new safety area with 37,000 square feet of articulated concrete block. Open blocks strung together with cables create a flexible mat that moves with the waves, Andersen explains. Saltwater grasses were planted in the open blocks, and now the area looks like a solid grass shoreline.

Engineers recommended the articulated block system after computer modeling projected that it would protect the shoreline against erosion for 75 years. They also tested large rocks deployed as riprap, but that design only yielded an estimated 50-year lifecycle. In addition, open crevices between the rocks would have supported mangroves, which could have become a maintenance and obstruction issue.

Since it was completed in April 2016, the system has been tested by two hurricanes — Matthew in fall 2016 and Irma last September. In both cases, the articulated block wall worked without any loss of the improved shoreline, and airport operations resumed the next day.

Seagrass Island & Marsh Restoration

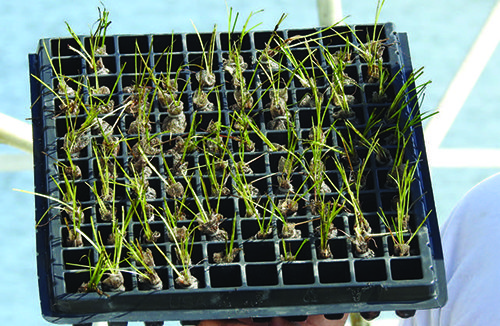

Crews filled a deep hole in the estuary along the runway’s north shoreline to create a shallow one-acre area for the new seagrass island. Aquatic restoration specialists from Sea and Shoreline harvested the seagrasses from the fill area and grew them at the company’s facility in Ruskin until the seedlings were large enough to be transplanted.

They encased the seedlings in circular wire cages to protect the tender plants until their roots were well established and to prevent manatees, turtles and pinfish from eating or uprooting the new plants, explains Andersen.

The seagrass mitigation island is now the only new portion of the lagoon where the seagrasses are thick, and the area is now rich with aquatic life such as crabs and conchs, she reports.

Another key environmental project occurred south of the airport, where crews helped restore balance to a 23.6-acre saltwater marsh along the Banana River. A berm created as part of a local mosquito control program had isolated the marsh from the nearby river, causing it to become a predominantly freshwater marsh that was consequently invaded by non-native plants. The airport sponsored efforts to clear away and mulch the invasive tree species and replace them with native Florida plants. It also installed a new system of pipes that allows personnel to flush or dry out the marsh at the appropriate times in the mosquito lifecycle to help control the population.

Before any of the work could begin, the airport authority had to purchase the property from an out-of-state owner. Because it used federal funds to do so, COI is responsible for monitoring and maintaining the improvements for five years, notes Powell. The newly improved area is adjacent to similar marshes already owned by the county.

Educational Opportunity

In addition to its four mitigation projects, the airport also launched an outreach effort by partnering with the biology program at Florida Institute of Technology, in Melbourne, FL. Since March 2016, graduate and undergraduate marine biology students under the leadership of Professor Jon Shenker have been sampling the seagrass mitigation area and mosquito saltwater marsh. Every six months, students monitor the health of the seagrasses and sample fish in the area.

Andersen notes that this partnership and the additional monitoring it provides are more examples of COI going beyond the requirements outlined in its permits.