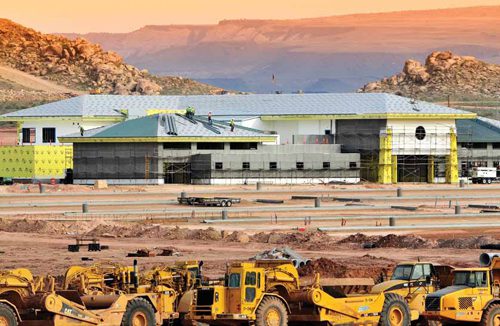

In January, the new St. George Municipal Airport (SGU) officially became a reality – and one of only two greenfield airports constructed in the nation in the last decade. The $159 million terminal and airfield replaced the city’s former airport, which was perched on 274 acres atop a mesa with no room for expansion. Built prior to Sept. 11, 2001 and limited by existing infrastructure, St. George’s previous airport failed to meet all of the FAA safety requirements for commercial airports.

In contrast, the site for the new airport is approximately five times larger. The runway is twice as wide at 150 feet and one-third longer at 9,300 feet – enough to receive jet aircraft, serve more destinations at greater distances and attract more airline carriers. In addition, the runway was designed so the airport can extend it to 11,500 feet, if needed. Together, the airside and terminal projects represented the biggest building program in the city’s history; so it was a significant achievement when they were completed on schedule and $1 million under budget.

Officials expected a crowd of about 3,000 at the dedication and open house but estimate that three times that many came. Interest was so keen in the project’s final results that traffic in the mountain valley backed up for more than five miles. Visitors continued to filter through the facility after the ceremony ended and the first official passengers departed on chartered flights provided by SkyWest Airlines, a subsidiary of SkyWest, Inc. based in St. George.

Officials expected a crowd of about 3,000 at the dedication and open house but estimate that three times that many came. Interest was so keen in the project’s final results that traffic in the mountain valley backed up for more than five miles. Visitors continued to filter through the facility after the ceremony ended and the first official passengers departed on chartered flights provided by SkyWest Airlines, a subsidiary of SkyWest, Inc. based in St. George.

Even after the crowds left and the associated Washington County Economic Development Summit ended, Mayor Dan McArthur continued to receive compliments about the airport. One person characterized the dedication ceremony as the county’s “marquee event of the century.” Another thanked him for allowing better access to business travel.

In the Beginning …

In the Beginning …

The idea for the new airport traces back to the mid-1980s, when city officials began evaluating whether the former airport could serve the community’s long-term needs. The city that was founded by Mormon prophet/colonizer Brigham Young currently has a population of 71,000+ and is in a county with an average annual growth rate of 3.9%. Year-round golf and proximity to national parks (Zion, Bryce Canyon and the Grand Canyon) attract businesses, retirees and tourists to the arid region.

A 2006 FAA press release naming SGU as a grant recipient explained that a replacement airport was necessary because St. George was the nation’s fastest-growing metropolitan area from 2000 to 2005. Expanding the former airport, which was perched on Black Hill Mesa and bounded by cliffs, simply wasn’t possible. After evaluating 15 locations in a 50-mile radius, city officials chose a location that had already served as a landing strip: 1,200 acres of rolling high desert on a mesa five miles southeast of downtown.

A 2006 FAA press release naming SGU as a grant recipient explained that a replacement airport was necessary because St. George was the nation’s fastest-growing metropolitan area from 2000 to 2005. Expanding the former airport, which was perched on Black Hill Mesa and bounded by cliffs, simply wasn’t possible. After evaluating 15 locations in a 50-mile radius, city officials chose a location that had already served as a landing strip: 1,200 acres of rolling high desert on a mesa five miles southeast of downtown.

|

factsfigures Airport: St. George (UT) Municipal Airport Project: Replacement Airport Cost: $159 million Program Management: Jacobs Engineering Group Benefits: Larger, expandable facilities and runway; ability receive jet aircraft, serve more destinations at greater distances & attract more airlines. Site Study, Environmental Assessment & Master Plan: Creamer & Noble/Barnard Dunkelberg & Company Airfield & Airside Design: PBS&J with Creamer & Noble Landside Design & Off-site Design Consultant: Creamer & Noble Paving & Lighting design: PBS&J with Creamer & Noble Finish Grading Design: PBS&J with Creamer & Noble Terminal & ARFF Building Designs: Reynolds, Smith & Hills Construction Management (Terminal & ARFF): Reynolds, Smith & Hills Replacement Water Tank: Sunroc Finish Grading: Quality Excavation Grading & Drainage: R.E. Monks Construction Terminal Building Construction: Westland Construction ARFF Construction: Ascent Construction Local Subcontractor, ARFF design: Campbell & Assoc. Local Subcontractor, Terminal: Mesa Consulting Structural Engineering for Terminal & ARFF: Reaveley Engineers Westside Joint Utility Trench Construction: Desert Hills Testing & Quality Control Services: Landmark Testing & Engineering Navaid Engineering & Airspace Feasibility Study: ASRC Research and Technology Solutions Airfield, Roadway & Parking Paving/Lighting: Extension of Joint Utility Trench to Navaids: Quality Excavation Airfield Lighting & Navaids: Astronics DME Corp. Airport Water Tank: Alpha Engineering Co. On-site Water Line: Desert Hills Construction Off-site Sewer & Water Construction: Quality Excavation Baggage Handling: The Horsley Company Ticket counter conveyor: The Horsley Company Boarding Bridge: JBT AeroTech Terminal Seating: Arconas Interior Furnishings Specifications: Hamilton Park Interiors |

Fortuitous Timing

The bulk of funding, $123 million, came from the FAA, specifies airport manager Rick Crosman. The city also received $3 million in American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funds for the terminal building. The remaining $33 million was local funding: $10 million from Washington County’s transient room tax and $23 million from city transportation and water/sewer funds. Additional post-program proceeds are expected from the sale of the original airport property.

From a cost perspective, SGU’s timing was good. With the recession causing construction prices to plummet, bids submitted to the city were 45% to 50% below 2007 estimates, explains Larry Bulloch, public works director and program manager for the city of St. George. Value engineering and a design-bid-build or fast-track/phased approach helped further reduce costs.

Because the project ultimately came in under budget, the airport was able to add most of the items on its list of extras, including a Jetway Passenger Boarding Bridge from JBT AeroTech and a 47-foot oval baggage carousel from The Horsley Company.

Starting from Scratch

Building a greenfield airport and moving existing operations from one location to another was “extremely intense,” Bulloch relates. Crews needed to bring in utilities, water, sewer and communication connections from miles away. Water service included installation of a 2-million-gallon water tank; sanitary service provisions required 60,000 linear feet of 18-inch sewer line. In all, Bulloch estimates the city worked with about 90 companies and signed roughly 40 contracts.

Crosman describes the development process as “very complex” and requiring an “extraordinary” amount of coordination. “There were many challenges to overcome – from property acquisitions to financial controls,” he explains. “Coordination and schedule were of paramount importance for cost control and execution of the individual projects within the new airport program.”

In addition to Jacobs Engineering Group acting as the overall program manager, about 15 consultants participated in the project. “We were able to basically divide and conquer,” Bulloch says. “We broke the program down into smaller pieces and hired individual consultants to manage those pieces.”

Weekly meetings were held to facilitate communication and cooperation among all the stakeholders and ensure that decisions were made on a timely basis. “Everyone wanted this project to be successful, and everyone did everything they could to make sure it was,” says Steve Domino, Jacobs’ senior program manager.

The program was divided into three work areas: 1) the runway, taxiway, airfield and associated elements such as grading and drainage, fencing, paving and lighting; 2) landside elements including utilities, roadway work, parking lots and landscaping; and 3) terminal and Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting (ARFF) facility architecture.

Construction of the terminal building alone required 95 phases and 455 days.

Blasting, Grading & Draining

PBS&J, an Atkins company, supervised three phases of airfield construction and partnered with Creamer & Noble Engineers to design and construct the airfield.

To make way for the runway, 30 feet of solid rock had to be blasted away. About 400,000 cubic yards of the blasted material was later used as the structural base under building and pavement areas.

“Very little material was brought on site, and hardly any left the site,” explains PBS&J project manager Ben Seaman.

The airfield project team also had to re-contour 4.7 million cubic yards of earth. “We encountered a lot of clay materials that needed to be removed from pavement and building areas,” Seaman recalls. Because the clays were so expansive, the terminal and ARFF building footprints were excavated at a minimum of 17 feet below the finished grade, he notes. If the clays had not been removed and water reached them, they could have pushed the foundation up and damaged the terminal, Seaman explains. Crews consequently over-excavated any airfield area where clays were found, he adds.

“We ended up with so much clay that we needed to have waste areas,” Seaman recalls. Some of the clay was used to form an expanded runway safety area north of the runway, which was capped by eight inches of improved material.

Apron grading and storm water drainage systems, designed by PBS&J subconsultant Creamer & Noble, included the installation of 5,000 linear feet of storm drain ranging in diameter from 18 to 72 inches. Kirt McDaniel, the company’s lead design engineer, enjoyed working at the greenfield site, unhampered by obstacles typically found at existing airports.

Readying the Airfield

The airfield portion of the project included a 9,300-foot runway, full-length parallel taxiway on the east side, partial-length taxiway on the west side, airfield lighting and signage, an electrical vault and aprons for the terminal, FBO and general aviation areas.

During the initial design phase, consultants evaluated current and future market demands, and projected the airport’s future fleet mix. The runway’s initial weight-bearing capacity was predicated on regular service from aircraft in the Canadair Regional Jet family and occasional use by larger aircraft, up to B-737s and the like. As such, it required about four inches of asphalt runway over an engineered sub-grade construction. If service from larger aircraft becomes more frequent, the airport can overlay the existing runway surface with four more inches of asphalt to minimize additional flexing and wear and tear. With the exception of runway thickness, all other parameters of the airport were designed to accommodate regular service from larger aircraft.

Landing a plane at the former airport was often described as landing on an aircraft carrier without an ocean, because there was very little room for navigational aids. The new airport location offers plenty of room out in the dirt. A glide slope mast and localizer are angled from the runway about 71/2° to facilitate a turn in the approach path, notes Seaman.

Astronics DME provided the airfield navaids, including a medium-intensity approach lighting system (MALSR) and precision approach path indicator (PAPI) – the latest FAA E-spec equipment, note project team members. Helix Electric, acting as a subcontractor to Quality Excavating, installed the systems. Astronics also provided runway and taxiway lighting, airfield signage and vault equipment, including power regulators and control system. LED fixtures were used on the taxiway edge lights.

Astronics DME provided the airfield navaids, including a medium-intensity approach lighting system (MALSR) and precision approach path indicator (PAPI) – the latest FAA E-spec equipment, note project team members. Helix Electric, acting as a subcontractor to Quality Excavating, installed the systems. Astronics also provided runway and taxiway lighting, airfield signage and vault equipment, including power regulators and control system. LED fixtures were used on the taxiway edge lights.

According to Eric Locke, Astronics’ sales and marketing manager, the work was rather straightforward. “Like any project, the challenges were meeting the construction schedule and the requirements for getting product on site, and reacting in a timely and appropriate manner to project changes (including additions) that developed as the project evolved,” Locke recalls.

Indoor Canyon & More

To develop a theme for the architecture of the 34,000-square-foot terminal and 11,000-square-foot ARFF station, Reynolds Smith & Hills (RS&H) worked with community stakeholders and studied the history of “Utah’s Dixie.”

“Our architecture is not an expression of our own feelings of what the terminal should be, but what the community is searching for,” says Michael Spitzer, head architect and project manager for RS&H. “The city council was very involved in forming the design. From the beginning, the participation was very exciting.”

Taking city council members on a three-day trip to visit other airports helped make the design process “much more focused,” notes Spitzer.

The size and color of the terminal’s exterior was designed to complement buildings in St. George’s historic downtown district, which is awash in reds, light greens and tans. Designers also took inspiration from the strong geological formations that surround the airport. The interior terminal space that connects the landside and airside replicates a canyon, similar to those found in nearby Zion National Park. Different shades of warm wood panels, 28 feet high, curve like a slot canyon accommodating a winding river.

A large window presents views of Pine Valley Mountain, and clerestory windows provide indirect lighting. Deep roof overhangs offer protection from summer’s dry heat.

|

former SGU (620 South Airport Road)

new SGU (4550 South Airport Parkway)

|

The hold room has a mix of seating styles, including a Flyaway cluster from Arconas, with six seats around a triangular table.

Like Zeller, Linda Briggs Ashton of Hamilton Park Interiors was also struck by the work of the design team. “I think they did a beautiful job of bringing the outside in,” comments Briggs Ashton. “When you walk into the airport, it feels like it belongs there. It’s a natural setting, not something taken from somewhere else and dropped in the middle of St. George.”

A 35-foot ticket counter, with gravity roller conveyors from The Horsley Company that feed baggage to the make-up area, adds to the aesthetic appeal.

Local artwork was incorporated throughout the interior. SGU’s collection includes two oil paintings, two bronze sculptures, seven mounted photographs, a stained glass installation and several reproductions of paintings on ceramic tile. The largest work, a 35-foot-by-7-foot mural, hangs in the passenger departing/arrival lounge on seven panels. An artwork committee chose the pieces not only as a function of the airport, but also as part of the wider community. The “interconnection and interdependence of the area’s histories – natural, human and cultural – as well as the tenacity required to thrive in a desert environment” were also considered during the selection process

A meeter/greeter lounge known as “the garden” offers a place for visitors to wait for arriving passengers. The two-story space features natural light from the skylight above, a water feature and natural greenery. The goal was to create an all-seasons area that would “feel like the outdoors,” explains Spitzer. But the enclosed courtyard also provides flexibility for future expansion. If the airport needs more space, the garden can be removed from the center of the terminal.

The building’s second floor includes a meeting space for large groups and an observation room, where the public can view the airfield.

As the airport grows, every facet of the terminal building should be ready for expansion, Spitzer relates, noting that the terminal was designed to double in capacity to meet the airport’s needs well beyond 20 years.

The airport’s ARFF building is about 300 feet way from the terminal. Although the two are distinctly different in function, they share the same architectural vocabulary. The ARFF facility houses a three-bay fire station, administrative offices and maintenance facilities. The Index B airport’s Oshkosh Striker, capable of carrying 1,500 gallons of water and foam fire suppressant, is at home in the new facility.

Prepping for the Future

In many ways, building the new SGU meant building for the future. “I think the airport will have a large economic impression upon the southern Utah region,” Seaman says. “I think it definitely will be a benefit for them.”

SkyWest Airlines has already upgraded its previous twin-engine turboprop service between St. George and Salt Lake City to jet service, thus reducing flight time for passengers. It also plans to begin United Express service between St. George and Los Angeles in early March. The new roundtrip will operate six days a week aboard the EMB 120 Brasilia, providing direct access to the West Coast and United Airlines’ global network via SGU.

With almost 1,000 more acres available on the new airport’s site, Crosman notes the potential to cultivate growth in nearly all facets of aviation services. General aviation, for example, will have more than 70 hangars.

In Retrospect

Given the project’s early challenges, McArthur says it sometimes felt as if the replacement airport might never happen. In the end, though, it all came together: financing, costs and schedules, construction issues, airspace procedures, TSA elements and FAA certifications, chronicles Crosman. “(The team) worked together to deliver an on-time, under-budget airport project that performed perfectly on opening day,” he raves.

Crosman is proudest of the tremendous efforts by the project team to get the job done. “We had a tremendous working relationship between city departments, consultants and contractors, and, most importantly, the state and FAA that enabled us to conquer the obstacles and complete a successful program,” he relates. “The new airport turned out to be everything we had hoped for and more.”

Enthusiasm for building a new airport from the ground up ran high throughout the project team.”You don’t work on a project like this very often,” says McDaniel, who performed the site study and master planning starting in 1998. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” Spitzer agrees.